VOICE ONE:

This is SCIENCE IN THE NEWS, in VOA Special English. I’m Bob Doughty.

VOICE TWO:

And I’m Sarah Long. This week: the life story of Elisabeth Kubler-Ross, the doctor who gave a voice to the dying.

(THEME)

VOICE ONE:

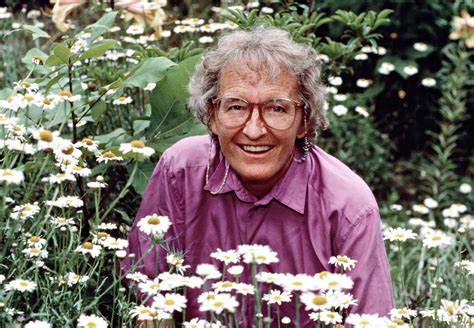

For most of her life, Elisabeth Kubler-Ross studied death. She became famous. She changed the way many others in the medical profession care for the dying.

In recent years, Doctor Kubler-Ross could speak from personal experience. She had a series of infections and strokes. But she continued her work, even as her health weakened. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross died last month at her home in Arizona, in the American West. She was seventy-eight years old.

VOICE TWO:

She was born Elisabeth Kubler in Switzerland in nineteen twenty-six. She was born at the same time as her two sisters. Back then, giving birth to triplets was far riskier than it is now. All three girls and their mother survived. But Elisabeth weighed less than a kilogram at birth.

After high school, she became interested in the process of death. She worked without pay at a hospital in Zurich. She helped care for World War Two refugees. Later she traveled through Europe. She visited countries affected by the war. She also visited a Nazi German death camp in Poland. It was there that she decided she would become a doctor of psychiatry and help people deal with death.

VOICE ONE:

Elisabeth Kubler studied medicine at the University of Zurich. She became a doctor in nineteen fifty-seven. She married another doctor, Emmanuel Ross. In nineteen fifty-eight they moved to the United States. She worked for a couple of years at a hospital in New York City.

Doctor Kubler-Ross said the lack of interest in dying patients at the hospital shocked her. She demanded better care. She developed programs to provide emotional support.

In nineteen sixty-one, Elisabeth Kubler-Ross had her first chance to teach others about what she found so important. She moved West to teach at the University of Colorado Medical School.

She knew that few doctors wanted to talk about the subject of death. Most usually kept the truth from dying patients. But Elisabeth Kubler-Ross wanted medical students to explore what she called the “greatest mystery in medicine.”

(MUSIC)

VOICE TWO:

There was very little written about the subject of death. But she had met a young cancer patient, a teenage girl with leukemia. The teenager had spoken openly and emotionally about her fear. She also expressed anger that her family was not preparing for the unavoidable.

Doctor Kubler-Ross invited the girl to be a guest speaker in class. The doctor told her to be completely honest, so the medical students could learn what it is like to be sixteen and dying.

Many of those future doctors cried. Word spread about this unusual lesson organized by Doctor Kubler-Ross. Her medical classes became very popular. Students of religion and members of the clergy also began to attend. So did social workers.

In nineteen sixty-five, Doctor Kubler-Ross began to teach at the University of Chicago Medical School. It was there that she began a series of classes that led to her famous book in nineteen sixty-nine called “On Death and Dying.”

VOICE ONE:

Some religion students had asked her for help in the study of death. She set up meetings with dying patients. She asked them questions while the students observed from another room.

Other doctors said patients, especially the young, should be sheltered from all talk of death. But Doctor Kubler-Ross said dying patients knew when they were being lied to, and that these lies had a terrible effect. She said dying patients often felt alone, like they had done something wrong.

VOICE TWO:

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross had talked to enough people to develop a theory. She found that many people go through five stages when they learn they are dying. The first reaction usually is denial. In time, denial generally turns into anger, the idea of “why me?”

People often next go through a stage that Doctor Kubler-Ross called bargaining. They might seek intervention from a higher power. Or they might think they can avoid death by changes in the way they live. When bargaining fails, a person may begin to think of all that will be lost and left undone, which leads to depression.

The last part of this process that Doctor Kubler-Ross described is acceptance. Generally, she found that people at the fifth stage mainly seek peace and rest. They disconnect, to different extents, from the world around them.

VOICE ONE:

The work of Elisabeth Kubler-Ross first appeared in a popular magazine. Life magazine published a story about a woman who criticized the way doctors treated her at the University of Chicago teaching hospital. This was one of the dying patients interviewed by Doctor Kubler-Ross.

Hospital administrators were not happy. They said the hospital wanted to be known for saving lives. The hospital would not let its doctors attend any more of the lectures about death.

Still, the article in Life magazine made Elisabeth Kubler-Ross famous. She received speaking invitations from across the United States.

(MUSIC)

VOICE TWO:

The force of the movement that she began is still felt today through programs like hospice care. A hospice is a home for people who are very sick and have no possibility for a cure. Doctor Kubler-Ross did not start hospice care in the United States, but her work provided guiding ideas.

The Hospice Foundation of America says hospices do not try to lengthen or shorten life. They try to make the final days as comfortable as possible. Hospices provide support to family members as well.

The teachings of Elisabeth Kubler-Ross dealt not only with death, but also with life. She often said the people who died most peacefully were those with the least regret about how they had lived.

VOICE ONE:

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross studied the process of dying until she was too sick to continue. She became especially interested in the idea of life after death. She and other doctors interviewed thousands of patients with near-death experiences. She said the stories of what the people experienced before doctors had saved their lives were all similar.

They usually said they experienced a freedom from pain, and a sense that they were floating above their bodies. Even so, they could often remember the words and actions of medical workers in the room.

Doctor Kubler-Ross reported that many people also spoke of moving toward a light or a feeling of warmth. They remembered that this felt so peaceful, they did not want to return.

As a result of these interviews, Doctor Kubler-Ross reasoned that there was some kind of life after death. She stated this as fact at a meeting of psychiatrists in nineteen seventy-three. She was widely criticized. Later, she spoke of spirits that served as her “guides.” As a result of statements like these, her position as a scientist suffered greatly.

VOICE TWO:

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross left hospital work to further explore her theories about life after death. She also became interested in the study of what are known as out-of-body experiences. These new interests caused tension in her marriage. Her husband divorced her and took their two children to live with him. Years later, though, at the end of his life, he moved to Arizona where Doctor Kubler-Ross and her son took care of him.

In the late nineteen seventies, Elisabeth Kubler-Ross opened a center in California. Later she opened one in Virginia where she mainly worked with people with AIDS, especially babies. Both centers burned. In both cases, police believed the fires had been set.

The Virginia center burned in nineteen ninety-four. The following year, Doctor Kubler-Ross had a series of strokes. The last one limited her ability to move. But she continued to write books. She spent her remaining years in Scottsdale, Arizona, to be near her son. In two thousand-two, she moved into an assisted-living center.

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross was with friends and family when she died last month, on August twenty-fourth. Her death was described as peaceful.

(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

SCIENCE IN THE NEWS was written by Caty Weaver. Cynthia Kirk was our producer. This is Bob Doughty.

VOICE TWO:

And this is Sarah Long. If you would like to send us e-mail, write to special@voanews.com. And join us again next week for more news about science, in Special English, on the Voice of America.