For more than 50 years, photographer Horace Poolaw captured the lives of members of his American Indian tribe.

Now, The National Museum of the American Indian is showing the American Indian photographer’s rare work.

The exhibit is called “For a Love of His People: The Photography of Horace Poolaw.” Poolaw’s photos show the cultural assimilation that was taking place in American Indian communities during his lifetime.

Poolaw was a member of the Kiowa tribe. He took pictures of American Indian subjects. He used pictures to form a history of his friends, family and events important to them.

Linda Poolaw is his daughter from his second marriage. One of the 80 photos in the exhibit, she said, is of her and her older brother, Robert coming home from school.

“He put cowboy hats on our heads and gave us pistols to hold,” Linda remembers. Whether the photo was meant to be ironic or not, Linda is not sure. All she knows is that she never much cared for it.

Robert “Corky” and Linda Poolaw (Kiowa/Delaware), dressed up and posed for the photo by their father, Horace. Anadarko, Oklahoma, ca. 1947. 45HPF57 © 2014 Estate of Horace Poolaw. Reprinted with permission.

“No, it’s not because of the ‘cowboyness’ of it or the whiteness or racism or anything like that,” she said. “It’s just that Dad made us pose for him all the time. We had to be still. We had to wait for him to get the shot just right when all we wanted to do was go play.”

From tipi to mainstream

Horace Poolaw was born in 1906 in Mountain View, Oklahoma. Until the late 19th Century, Oklahoma’s Indian Territory belonged to tribes native to the area or that had been sent there from other parts of the country.

Poolaw’s tribe is called the Kiowa Comanche. They lived with the Apache tribe on a reservation that covered 1.2 million hectares of land.

But 20 years later, a law known as the Dawes Act permitted Congress to divide the land. Individual Indians were given their own land. The rest was opened up to non-Native settlers.

Horace Poolaw lived with his parents in a traditional tipi early in life. His father, Kiowa George, was the son of a warrior. Poolaw’s mother was descended from a Mexican woman who had been captured during a Kiowa raid. They moved into a house that still remains with the family today.

Then, settlers from the east came to live in Mountain View. Photographer George W. Long moved there and became a mentor to Poolaw. He gave the young man his first camera.

His work

Poolaw’s photos captured images of Kiowa women wearing traditional American Indian clothes and Kiowas in cars with headdresses.

But he had very little money to make photographs.

“He developed his own pictures, even though there was no electricity or water in the house back in those days,” said his daughter Linda. “He had to send to Chicago for film and developing supplies.”

The high cost of photographic paper and film meant that Poolaw worked hard to get his pictures right on the first try. He developed only a small number of the photographs he took. And he took all of his photographs outdoors so he would not need lighting equipment.

“We were poor, dirt poor,” said Linda. “But we didn’t know it because everybody around us was poor too.”

Today, those postcards sell for as much as $50 on the internet.

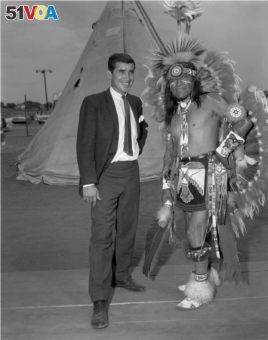

Danny Williams, left, and George “Woogie” Watchtaker (Comanche) at the American Indian Exposition. Anadarko, Oklahoma, ca. 1959. 45EXP17. © 2014 Estate of Horace Poolaw. Reprinted with permission.

Danny Williams, left, and George “Woogie” Watchtaker (Comanche) at the American Indian Exposition. Anadarko, Oklahoma, ca. 1959. 45EXP17. © 2014 Estate of Horace Poolaw. Reprinted with permission.

Poolaw continued taking pictures until the 1970s when his eyesight began to fail. In 1979, the Southern Plains Indian Museum in Anadarko organized an exhibit of his photographs. It would be the only showing of his work during his lifetime.

In the late 1980s, Poolaw’s daughter Linda established a research program at Stanford University to archive and digitize her father’s work. When her father died in 1984, he left behind 2,000 photographic negatives.

Today, art historians and critics consider Poolaw’s work equal to many better-known photographers working in the western United States in the early 20th Century. His photographs are often described as documenting the change from traditional to mainstream ways of life for American Indians.

I’m Dorothy Gundy. And I’m Marsha James.

Cecily Hilleary reported on this story for VOANews. Marsha James adapted her report for Learning English. Mario Ritter was the editor.

_____________________________________________________________

Words in This Story

assimilation – n. to fully become part of a different society, country, etc.

pistols – n. a small gun

exhibit – n. a collection of objects that have been put out in a public space for people to look at

ironic – adj. relating to or characteristic of a famous person or thing that represents something of importance

reservation – n. an area of land in the U.S. that is kept separate as a place for Native Americans to live

tipi – n. a tent that is shaped like a cone and that was used in the past by some Native Americans as a house

warrior – n. a person who fights in battles and is known for having courage and skill

mentor – n. someone who teaches or gives help and advice to a less experienced and often younger person

headdress – n. a decorative covering for your head

photographic negatives – an image on a photographic film that shows dark areas as ligh and light areas as dark, from which the final picture is printed

mainstream – n. the thoughts, beliefs, and choices that are accepted by the largest number of people

We want to hear from you. Write to us in the Comments Section.