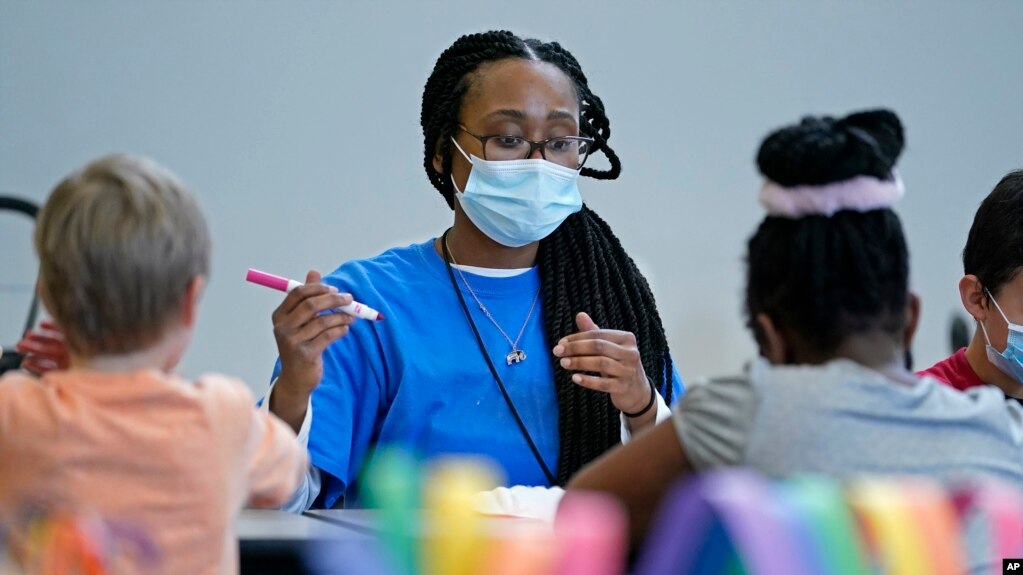

Kiara Beard works with children in a before- and afterschool program operated by the YMCA of Middle Tennessee in Wednesday, March 16, 2022, in Nashville, Tenn.

As students return to classrooms in the United States, many parents are still not able to return to work. They are finding that after-school childcare programs are in short supply.

School-based providers list difficulties in hiring and keeping workers as the biggest reasons they have not fully recovered from pandemic shutdowns. Providers say they are as worried about the situation as the parents who are without childcare.

“We’re in a constant state of flux. We’ll hire one staffer and another will resign. We’ve just not been able to catch up this year,” said Ester Buendia. She is assistant director for after-school programs at Northside Independent School District in Texas.

Before the pandemic, the local after-school program Learning Tree had 1,000 workers. They served more than 7,000 students at about 100 elementary and middle schools. Today, there are fewer than 500 employees serving about 3,300 students. More than 1,100 students are on waiting lists for the program. It provides educational, recreational and social activities every school day, outside of school hours.

Studies suggest parents, mostly mothers, are staying home for their children because they are unable to find after-school programming. That causes worker shortages at such programs that depend heavily on women to run them.

“There’s no doubt really that these after-school programs — the lack of after-school programs — are limiting women in particular being able to reenter the workforce,” said Jen Rinehart. She leads planning and programming for the nonprofit group Afterschool Alliance.

“If women don’t return to the workforce, then we don’t have the staff we need for these after-school opportunities, so it’s all very tangled together,” she said.

An Afterschool Alliance study found a record high of 24.6 million children were unable to enter a program at the end of 2021. The researchers looked at more than 1,000 program providers. They found 54 percent had waiting lists, a much larger share than in the past.

Wells Fargo reported that labor shortages in childcare are more severe than in other industries also struggling to find dependable employees. Employment was 12.4 percent below its pre-COVID-19 level at the beginning of March. That leaves an estimated 460,000 families forced to make other plans, the researchers found.

Erica Gonzalez of San Antonio got after-school care for her daughters who are in second and sixth grade. That permitted her to keep her job at a nonprofit and her husband, a teacher, to also coach.

Gonzalez had made sure to register her children for Learning Tree as early as possible. She also kept in contact with the girls’ schools through the process.

Gonzalez said, “We were really just kind of hoping and praying” for placement in the program.

The Afterschool Alliance survey found that 71 percent of programs had taken action to hold onto to its workers and appeal to job seekers. The most common measure was to increase wages. In some cases, programs used federal pandemic relief money in the form of childcare awards. Some also have offered free childcare for employees as well as extra money or paid time off.

Rinehart described a “tremendous unmet demand for after-school and summer programs” even before the pandemic. She said the health crisis has made the problem worse.

I’m Jonathan Evans.

Carolyn Thompson reported on this story for the Associated Press. Jonathan Evans adapted this story for Learning English.

__________________________________________________________________

Words in This Story

flux – n. change; fluctuation

doubt – n. a feeling of being uncertain

particular – adj. relating to one person or thing

opportunities – n. greater chances for success

tangled – adj. very involved; exceedingly complex

coach – v. to teach and train

tremendous – adj. astonishingly large, strong, or great