Across the United States, pandemic aid money is helping to fund a growing number of big-city schools with shrinking numbers of students.

When the money runs out in a few years, officials will face a difficult choice: Keep the schools open despite the financial difficulty, or close them, upsetting communities looking for stability for their children.

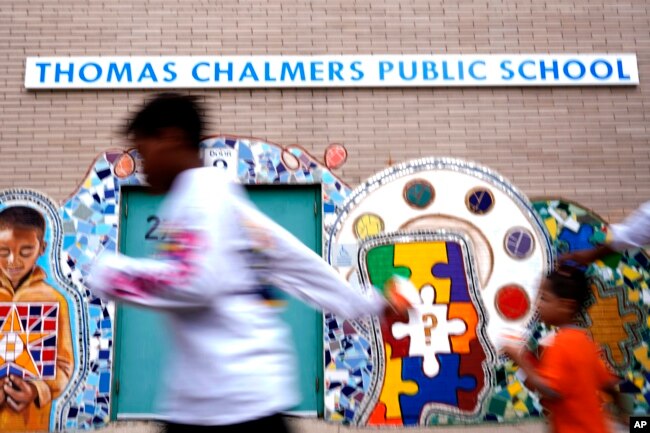

The summer program at Chalmers School of Excellence in Chicago, Illinois, offers one-on-one teaching that parents love. But school principal Romian Crockett worries the school is becoming too small. Chalmers lost almost one-third of its enrollment during the pandemic. Today, only 215 students attend Chalmers.

In Chicago, COVID-19 worsened enrollment declines that began before the virus. Some poor Black neighborhoods in the city, like Chalmers’ North Lawndale, have seen families leave in large numbers over the past 10 years.

The number of small schools like Chalmers is growing in many American cities. More than one in five New York City elementary schools had fewer than 300 students last school year. In Los Angeles, California, over one in four have fewer than 300 students. In Chicago, nearly one in three are that small. In Boston, Massachusetts, it is almost one in two. These numbers come from research by Chalkbeat and The Associated Press.

Many of these schools were not designed to be small. Educators worry there will smaller budgets in the coming years, even as schools continue to recover from the pandemic.

“When you lose kids, you lose resources,” Crockett said. “That impacts your ability to serve kids with very high needs.”

A state law prevents Chicago from closing or combining its schools until 2025. Across the U.S., COVID-19 relief money is helping fund shrinking schools. It is unclear what will happen to those schools when the funding runs out.

“My worry is that we will shut down when we have all worked so hard,” said Yvonne Wooden, who serves on Chalmers’ school council. “That would really hurt our neighborhood.”

The pandemic quickened enrollment declines in many districts. Many families started homeschooling or sought enrollment at charter schools and private schools. Some students moved away or stopped attending school for unknown reasons.

Many districts like Chicago give schools money for each individual student. That means small schools sometimes struggle to pay for costs like the principal, a counselor or building upkeep.

To deal with that, many school systems send extra money to small schools, taking money from larger schools. In Chicago, the district spends an average of $19,000 yearly per student at small high schools. Students at larger high schools get $10,000, Chalkbeat and the AP found.

Small schools are popular with families, teachers and community members because of their supportive environment. Some argue that districts should send more money into these schools. Many such schools are in Black and Latino neighborhoods that have been hit hard by the pandemic.

In 2013, 50 schools closed in Chicago. Most were in Black neighborhoods. The move damaged trust between locals and the district. It also hurt learning for students from poor families, researchers at the University of Chicago found.

When schools close, it is “devastating” for families, said Suleika Soto. She is with the Boston Education Justice Alliance, which supports underrepresented students.

“And then if parents don’t like it, then they’ll remove their children from the public school system,” she said.

Still, some city school systems losing students are considering school closures. Earlier this year, the school board in Oakland, California, voted to close several small schools despite protests.

In other cities, leaders have continued to invest in small schools.

Chicago received $2.8 billion in COVID-19 relief. It will use about $140 million of the money to help small schools this school year, officials said.

In Los Angeles and New York City, officials say they are centering their efforts on bringing students back into school, not closing them.

But federal relief money will run out in two years. Districts must use the money by September 2024. When the money is no longer there, it may be difficult for districts to keep small schools open.

“It’s a huge problem,” said Bruce Fuller, an education researcher at the University of California, Berkeley. “It’s going to be increasingly difficult for superintendents to justify keeping these places open as the number of these schools continues to rise.”

I’m Dan Novak.

Dan Novak adapted this story for VOA Learning English based on reporting by The Associated Press.

Quiz- Big US School Systems Are Losing Students

Start the Quiz to find out

_____________________________________________________________________

Words in This Story

stability — n. the quality or state of something that is not easily changed or likely to change

enrollment — v. to enter as a member of or participant in something

impact — n. the act or force of one thing hitting another

devastating — adj. causing great damage or harm

superintendent — n. a person who directs or manages a place, department, organization, etc.