Many schools in the United States are facing increased student behavioral and mental health needs. But parents and school officials are struggling to find out if some students’ problems are tied to the COVID-19 pandemic or are long-term problems.

Heidi Whitney is from San Diego, California. She has a daughter in middle school. The pandemic sent Whitney’s daughter into crisis. She was sleeping all day and awake all night. When in-person classes started, she was so tense at times that she asked to come home early.

Whitney tried to keep her daughter in class. But the girl’s condition worsened. She had to go the hospital and was diagnosed with depression and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a mental disorder.

As she started high school this fall, Whitney’s daughter was considered eligible for special education services because her disorders hurt her ability to learn. But school officials said it was hard to know how much of her behavior was a long term condition or the result of mental health problems caused by the pandemic.

“They put my kid in a gray area,” Whitney said.

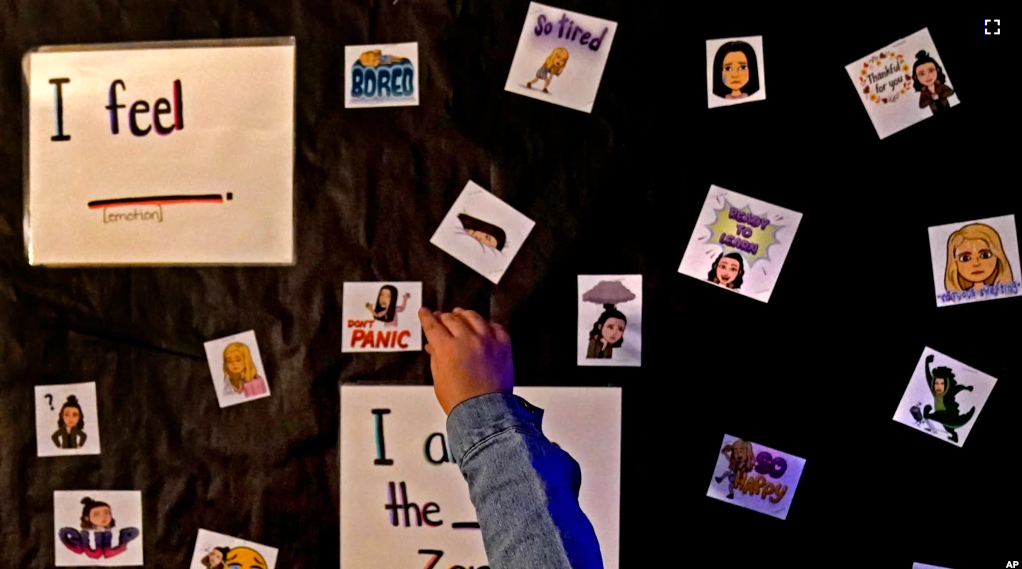

Officials in many schools who are dealing with increasing student mental health needs have been struggling with difficult decisions. They are trying to find out whether the problems they are seeing are temporary or are the sign of more serious disabilities.

Some observers say this puts pressure on parents trying to decide how best to help their children. The question is: If a child is not eligible for special education, where should parents go for help?

Rules require school officials to say how they will meet the needs of students with disabilities in Individualized Education Programs (IEPs). Some schools have struggled to catch up with mental health evaluations that were delayed in the early days of the pandemic. There is also a reported shortage of school psychologists.

Federal law says to be eligible for special education services, a child’s school performance must be suffering from one of 13 disability groups. They include autism, ADHD, learning disabilities like dyslexia, developmental delays, and emotional problems.

John Eisenberg is the director of the National Association of State Directors of Special Education. He said it is important not to send children who might have had a difficult time during the pandemic into the special education system.

“That’s not what it was designed for,” he said. “It’s really designed for kids who need specially designed instruction.”

He added: special education is not “for kids that might have not got the greatest instruction during the pandemic or have…other issues.”

The National Center for Education Statistics found about 15 percent of all public school students received special education services in the 2020-2021 school year.

Among children ages six and older, special education enrollment rose by 2.4 percent compared with the previous school year. The government numbers also showed a large drop in enrollment for younger, preschool-age students, many of whom were slow to return to school.

Some special education directors worry the system is taking on too many students. But others say the opposite is the case. They say schools are moving too quickly to dismiss parents’ concerns.

Some children are having evaluations pushed off because of worker shortages, said Marcie Lipsitt. She is an activist for special education in Michigan. She said, in one school district, evaluations came to a complete halt in May because there was no school psychologist to do them.

It can be difficult to know the differences between problems that started because of the pandemic and an actual disability, said Brandi Tanner. She is an Atlanta-based psychologist who has had many requests from parents seeking evaluations for possible learning disabilities, ADHD and autism.

“I’m asking a lot more background questions about pre-COVID versus post-COVID, like, ‘Is this a change in functioning or was it something that was present before and…gotten worse?’” she said.

Kevin Rubenstein is with the Council of Administrators of Special Education based in Missouri. He said it is important to have good systems in place to know the difference.

The federal government, he noted, has provided large amounts of COVID aid money to schools. Some of the money is for counseling and other support to help students recover from the pandemic restrictions.

But activists worry about what will happen to students who do not receive the help they might need. Children who do not get help might have more behavioral problems and fewer possibilities for life after school, said Dan Stewart. He is with the National Disability Rights Network.

Whitney, the mother from San Diego, said she is happy her daughter is getting help, including a case manager. She also will be able to leave class as needed if she feels nervous.

“I realize that a lot of kids were going through this,” she said. “We just went through COVID. Give them a break.”

I’m Dan Novak.

And I’m Faith Pirlo.

Dan Novak adapted this story for VOA Learning English based on reporting by The Associated Press.

Quiz- How Many Children Need Special Education after Pandemic?

Start the Quiz to find out

_______________________________________________________________

Words in This Story

diagnose –v. to formally recognize and identify something such as a disease

eligible — adj. able to receive of be chosen for something

gray area — n. a situation in which it is difficult to decide what is right and what is wrong

evaluation — n. to judge the condition of someone or some thing

autism — n. a disorder that begins in childhood and which causes problems for a person forming relationships and communicating

dyslexia — n. a condition that makes it difficult for people to read, write or spell

instruction –n. the process of teaching someone

enrollment — n. to process of formally asking to enter a program, school or university

background — n. the conditions that caused something to be the way it is

function — v. to work, perform a job or operate