It is widely known that students’ test scores decreased across the United States because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

But many parents do not know that their own child or children are among those whose scores have suffered.

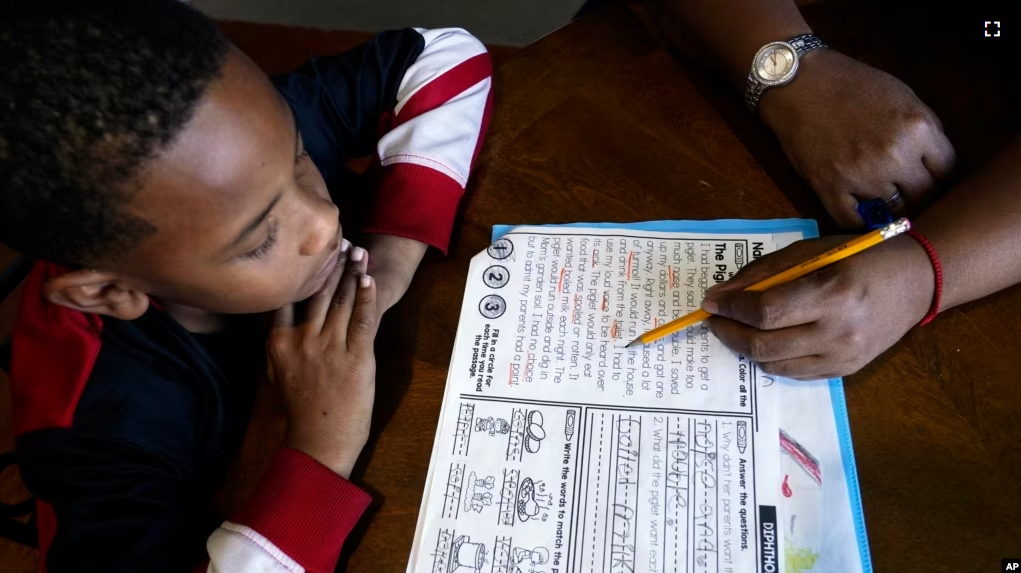

In Boston, Massachusetts, Evena Joseph did not fully understand how much her 10-year-old son was struggling in school. She found out only with help from somebody who knows the Boston school system better than she does.

Joseph is a Haitian immigrant. Her son, J. Ryan Mathurin, was in the 30th percentile in reading. That means 70 percent of students had stronger reading scores than him. But Joseph did not know how far behind her son was until a hospital where he was receiving treatment connected her with a bilingual aid.

“It’s only because I was assigned an educational advocate that I know this about my son,” Joseph said.

Schools have long faced criticism for failing to inform some parents about their kids’ progress in school. But after COVID-19 school closures, the importance of keeping parents informed has in many ways never been greater.

There are many chances to catch up, thanks to federal COVID aid. But it will take better communication with parents to help students get the support they need, experts say.

“Parents can’t solve a problem that they don’t know they have,” said Cindi Williams. She is co-founder of Learning Heroes, a nonprofit working to improve communication between public schools and parents about student progress.

In 2022, Learning Heroes questioned 1,400 public school parents around the country. The group found that 92 percent believed their children were performing at grade level. But in a federal survey, school officials said half of all U.S. students started this school year behind grade level in at least one subject.

The struggles that brought J. Ryan to the hospital for mental health treatment began in third grade. That was when he returned to in-person school after nearly a year of learning online. J. Ryan was getting angry in class, disrupting lessons and leaving the classroom.

J. Ryan showed these behaviors during English and other classes, including Mandarin and gym. He did better in math class, one of his stronger subjects. But Joseph said teachers never told her about her son’s problems with reading.

Last spring, she sought treatment for her son’s depression. She was helped at the hospital with the parent advocate who speaks English and Haitian Creole.

The advocate pushed to get J. Ryan’s scores from the tests given each fall to measure student learning. She explained to Joseph what it meant for J. Ryan to be in the 30th percentile in reading.

Before this year, schools in the Boston system could decide whether to share test scores with parents. But it is not clear how many were doing it. In the fall, Boston schools started a communications program to help teachers explain testing results to parents as many as three times a year.

Research shows there are many reasons teachers might not talk to parents about a student’s academic progress, especially when the news is bad.

“Historically, teachers did not get a lot of training to talk to parents,” said Tyler Smith. He is a school psychology professor at the University of Missouri. School leadership and support for teachers also make a difference, he added.

Teachers might also think that poorer parents do not care about their child’s progress, said Williams, the co-founder of Learning Heroes.

Without these discussions, parents only look at report cards. But report cards are considered to be subjective. They may not be the best signs of overall student success.

Many school systems have used their federal pandemic recovery money for summer school, tutoring programs and other actions to help students recover from the pandemic. But students have not used the extra help as much as educators had hoped. If more parents knew their children were behind academically, they might seek help.

After J. Ryan moved to a new school, Joseph stopped getting phone calls from the teacher complaining about his behavior. Joseph said her son is getting good treatment for his depression. But Joseph said she has not received a report card this year or the test scores that the district claims it is now sending to families.

She said, “I’m still concerned about his reading.”

I’m Dan Novak.

Dan Novak adapted this story for VOA Learning English based on reporting by The Associated Press.

Quiz – Some Parents Do Not Know Their Children Struggle in School

Start the Quiz to find out

_____________________________________________________________________

Words in This Story

advocate — n. a person who argues for or supports a cause or policy

survey — n. an activity in which many people are asked a question or a series of questions in order to gather information about what most people do or think about something

disrupt — v. to cause to be unable to continue in the normal way

depression — n. a serious medical condition in which a person feels very sad, hopeless, and unimportant and often is unable to live in a normal way

psychology — n. the science or study of the mind and behavior

subjective — adj. based on feelings or opinions rather than facts

district — n. an area established by a government for official government business

tutor — v. a teacher who works with one student