Japan is a nation known for its workers’ loyalty to their companies and lifetime employment. People who change jobs are often considered quitters, and that is seen as dishonorable.

But a number of “taishoku daiko,” or “job-leaving agents,” have started in the past several years. Their aim is to help people who want to leave their jobs.

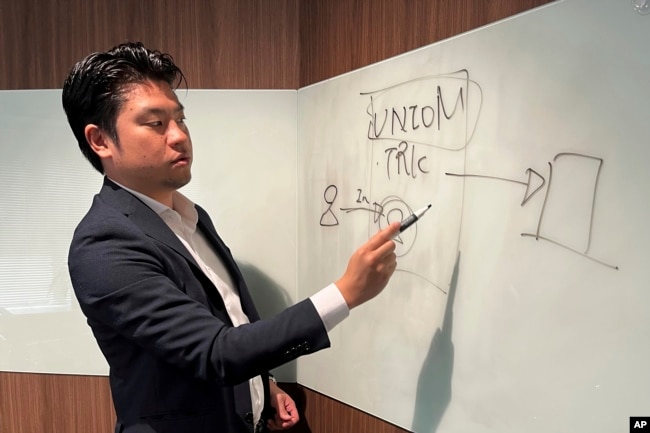

Yoshihito Hasegawa heads Tokyo-based TRK, whose Guardian service last year advised 13,000 people on how to leave their jobs with the fewest problems possible.

He said many people often stay in their jobs even when they are unhappy. They feel like they are sacrificing part of their lives for the greater good.

“It’s the way things are done, the same way younger people are taught to honor older people,” he said. “Quitting would be a betrayal.”

The company Guardian is a taishoku daiko service founded in 2020. It has helped many people, mostly young people in their 20s and 30s, escape less painfully from jobs they want to quit. It includes people who have worked anywhere from a law firm to a restaurant.

Nearly half of Guardian’s users are women. Some work for a day or two and then discover promises of pay or work hours were false.

Guardian charges $208 for its service. The cost includes a three-month membership in a union that will represent an employee in what can be a difficult negotiation process in Japan.

Most of Guardian’s users have worked for the small and medium-sized businesses that employ most Japanese. Sometimes people working for major companies seek help.

In many cases, bosses have a lot of influence over how things are run. Sometimes they will not agree to let a worker leave. Businesses face worker shortages in Japan and do not want to lose them.

Japanese law guarantees people the right to quit. But some employers are used to old employment methods and cannot accept that someone they have trained would want to walk away.

Agreeing with Japan’s work culture can be painfully heavy to some workers. They do not want to be seen as troublemakers and do not like to question supervisors or are afraid to speak up. They also might fear harassment after they quit. Some worry about the opinions of their families or friends.

Although most of Guardian’s users do not like to make their name public, a young man who goes by the online name of Twichan used the service. He sought help after he was criticized for his sales performance and became so depressed, he thought about harming himself. With Guardian’s help, he was able to quit in 45 minutes.

Lawyer Akiko Ozawa is with a legal office that advises people on leaving their jobs. But the office usually represents the companies. She has written a book on taishoku daiko. She said it might be hard to believe people cannot just pick up and leave.

Ozawa said that changing jobs is a major difficulty in Japan that requires a lot of bravery. Since there is a shortage of workers in Japan, finding and training replacements is difficult and bosses sometimes explode in anger when someone quits.

“As long as this Japanese mindset exists, the need for my job isn’t going away,” said Ozawa, who charges $450 for her service. “If you are so unhappy that you’re starting to feel ill, then you should make that choice to take control over your own life.”

I’m Gregory Stachel.

Yuri Kageyama reported this story for The Associated Press. Gregory Stachel adapted it for VOA Learning English.

_______________________________________________________________

Words in This Story

quit – v. to leave (a job, school, or career)

union – n. an organization of workers formed to protect the rights and interests of its members

harassment – v. to annoy or bother (someone) in a constant or repeated way