During the coronavirus pandemic, many schools struggled to keep a count of students whose families struggled with homelessness.

The number of children identified as homeless by schools nationwide dropped by 21 percent from the 2018-2019 school year to the 2020-2021 school year, federal data found. That decrease represented more than 288,000 students.

But it is likely there were many students whose schools did not know they were homeless.

By the time Aaliyah Ibarra started second grade, her family had moved five times in four years in search of housing. As she was about to start a new school, her mother, Bridget Ibarra, saw how much it was affecting Aaliyah’s education.

At 8 years old, Aaliyah did not know the alphabet. Her family’s struggles came during the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced Aaliyah to begin school online.

Online school was especially hard for Aaliyah because she was homeless. And, like thousands of other students across the country, her school did not know.

By not being identified as homeless, such students lose out on important support like transportation, clothes-cleaning services and other help.

Two years later, the effects have worsened. Students nationwide have struggled to make up for missed learning. And educators have lost important time identifying who needs the most help.

Schools are offering services like tutoring and counseling. But schools now have limited time left to spend federal pandemic assistance money for homeless students, said Barbara Duffield. She is director of SchoolHouse Connection, a national homelessness organization.

Many education leaders, Duffield said, do not even know about federal money meant to support homeless students. The federal support ends next year.

In Bridget Ibarra’s case, she chose not to tell the school her children were homeless. She said that teachers never asked. She was worried if officials knew the family was staying in a shelter, the family would face pressure to attend a different school that was closer to the shelter.

The stigma that comes with homelessness also can lead families not to tell anyone they do not have housing, Duffield said.

If schools cannot identify homeless children, “we can’t ensure that they have everything they need to be successful in school and even go to school,” Duffield added.

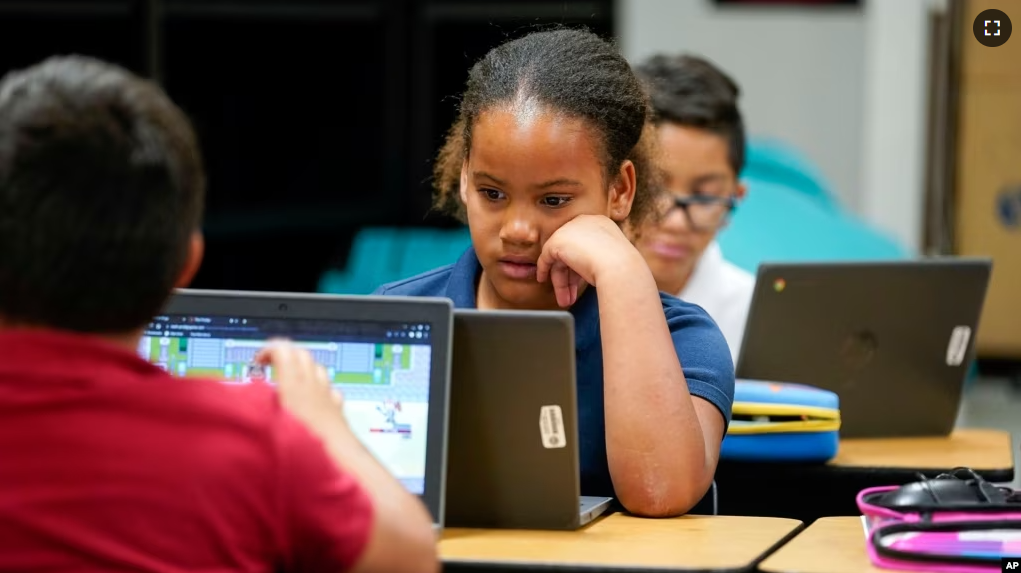

Aaliyah’s school is in Phoenix, Arizona. It continued with online learning for her whole kindergarten year. Aaliyah and her older brother spent most of their school days on computers in a temporary classroom at the shelter.

While the shelter helped the family meet their basic needs, Ibarra said she often asked the school for extra help for her daughter. She felt the school was giving all its attention to Aaliyah’s older brother because he is a special education student. That means he has been identified as needing extra educational support.

The school’s principal, Sean Hannafin, said school officials met often with the children’s mom. He said they offered the support they had available. But he said it was hard to know online which students required more help.

There is a federal law aimed at making sure homeless students have equal access to education. The law provides rights and services to children without a “fixed, regular and adequate nighttime residence.”

Many students are not identified as homeless when they sign up for school. At school, teachers or other school workers often notice students who may be dealing with difficulties at home. But with children learning online, teachers often could not see signs of problems.

Overall, the drop in the student homelessness count began before the pandemic. But it became greater when the pandemic began.

The percentage of enrolled students identified as homeless in the U.S. dropped from 2.7 percent in 2018-2019 to 2.2 percent in 2020-2021. Over that time, Arizona had one of the biggest drops in the number of students identified as homeless.

Eventually, Bridget Ibarra had to send Aaliyah to a different school after moving to find new housing. At Aaliyah’s new school, Frye Elementary, Principal Alexis Cruz Freeman saw how hard it was to communicate with families when children were not in classrooms.

Aaliyah has improved at her new school, Cruz Freeman said. She still has trouble saying and reading some words. But by the end of the school year, she was able to read a text and write four sentences based on its meaning. She is also performing at her grade level in math.

Cruz Freeman considers Aaliyah a success story in part because of her mother’s support. “She was an advocate for her children, which is all that we can ever ask for,” Cruz Freeman said.

I’m Dan Novak.

Dan Novak adapted this story for VOA Learning English based on reporting by The Associated Press.

Quiz- Schools lost track of homeless kids during the pandemic

Start the Quiz to find out

_____________________________________________________

Words in This Story

tutor — n. a teacher who works with one student

stigma — n. a set of negative and often unfair beliefs that a society or group of people have about something

kindergarten — n. a school or class for very young children

adequate — adj. enough for some need or requirement

text — n. the original words of a piece of writing or a speech

residence — n. the state of living in a particular place

ensure — n. to make sure, certain, or safe

access — adj. a way of getting near, at, or to something or someone

advocate — n. a person who argues for or supports a cause or policy