There are programs in the United States that aim to support families with their children’s early learning and development.

Home visiting programs try to improve early education at a low cost. The programs might expand with new federal money. The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) follows home visiting programs to see how effective they are and provides information about them on its website.

Isabel Valencia got experience with a home visiting program in 2022. During a trip to buy food with her two young children, somebody told Valencia about a program. She had moved to Pueblo, Colorado, a few months earlier and was feeling lonely. She had not met anyone else who spoke Spanish.

She learned about the Home Instruction for Parents of Preschool Youngsters program (HIPPY). HIPPY says it provides families with a trained support person who visits their home every week. The group shows them how to interact with their children using developmental activities.

The HIPPY program uses regular home visits and monthly group meetings to help parents learn how to improve early literacy and social and emotional skills. The workers went through the program themselves and often share the same language and background as the families they serve.

The program operates mostly in poor neighborhoods and through school districts and organizations for immigrant and refugee families, said Miriam Westheimer. She is chief program officer for HIPPY International, which operates in 15 countries and 20 U.S. states.

HHS has a program to provide money for Maternal, Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MEICHV) models. The agency has approved about 24 home visiting models. Some aim to help preschool children; others send social workers or nurses to support maternal and child health.

An estimated 17 million families nationwide could receive home visiting services. But in 2022, only about 270,000 did.

That is because the programs do not get enough money, said Dr. Michael Warren, of the Maternal and Child Health Bureau. That office oversees the MIECHV programs. “If more resources exist, more families can be served,” he said.

Federal spending on the MIECHV program is set to double from $400 million to $800 million yearly, by 2027. Beginning this year, the federal government will match $3 for every $1 in non-federal money spent on home visiting programs, up to a limit.

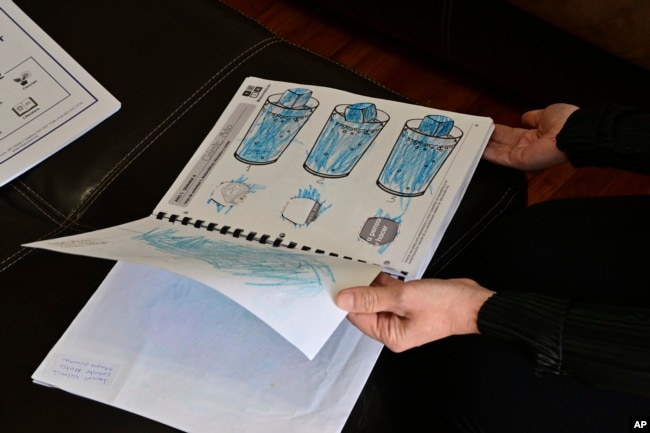

Home visitors supply books and materials to parents for developmental activities. They also supply diapers, and help them find food pantries, public assistance programs, and mental health professionals. They also explain the importance of talking, reading, and singing with young children, asking them questions, and praising them.

The home visitors also communicate a simple but important message to parents: Everything they need to help their children succeed is probably already at home.

A math lesson can be found among a bag of beans or a pocket of coins. Kids can practice reading skills by searching for objects around the house that start with a certain letter.

The most valuable thing, families and home visitors say, is the connection between parent and child. Parents also become better advocates for themselves and their children. Research suggests that children who went through home visiting programs are better prepared for school.

Home visiting is not meant to be a replacement for other early learning experiences. But supporters say it can help create a strong foundation, especially for the many families which find early education programs too costly.

Maria Chavez Contreras is home visiting program manager at the community-based organization that hosts HIPPY in Pueblo. She said kindergarten teachers say students who receive home visiting services have longer attention spans, follow instructions better and have more developed motor skills.

Fatema Zamani is a home visitor based in Denver, Colorado, who emigrated from Afghanistan in 2016. The parents she works with are all recent immigrant arrivals from Afghanistan. She said the kindergarten teachers are impressed with the children.

Her own four-year-old daughter is in the HIPPY program. She can say the alphabet, count, and identify shapes and colors.

“She is ready for preschool,” Zamani says.

I’m Dan Novak.

Dan Novak adapted this story for VOA Learning English based on reporting by The Associated Press.

Quiz – Home Visiting Programs Aim to Support Early Education

Start the Quiz to find out

_______________________________________________

Words in This Story

maternal –adj. related to mothers and motherhood

diaper –n. underclothing for babies

food pantry — n. (informal) a center where good can be got at either below market prices or at no cost

advocate — n. someone who speaks out in support of a cause or an organization

foundation — n. a base from which other things can be built

span — n. a period

motor — adj. related to movement