In South Korea, fewer women are having children. The high costs of housing and education make financial security a necessity. Social customs also dictate that a woman should be married before having a baby.

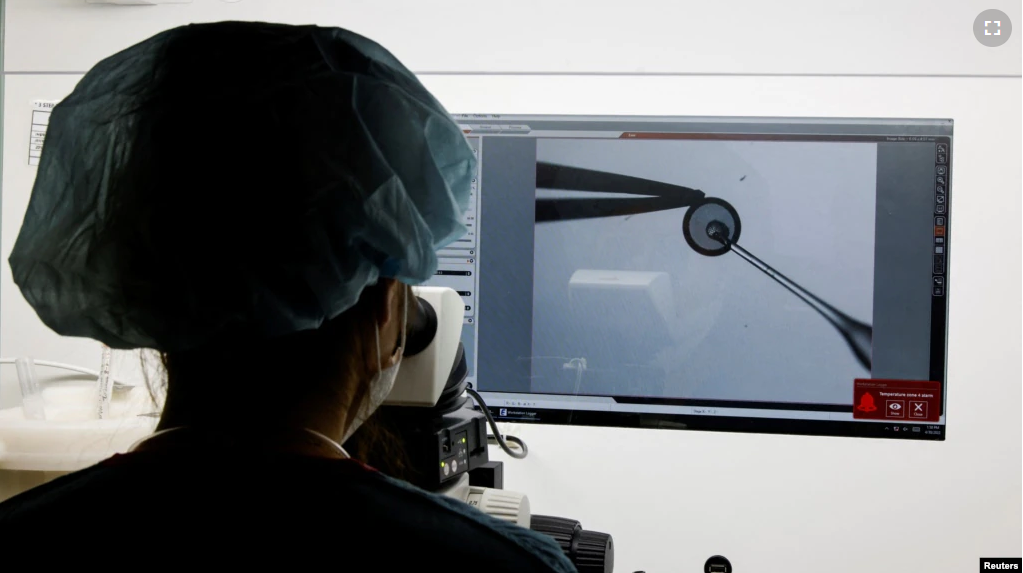

Lim Eun-young, a 34-year-old public servant, says she is not financially ready to start a family. She and her boyfriend are not married. They have been dating for just a few months. But Lim is worried about getting older and how that might affect her chances for pregnancy. So, in November, she had doctors remove some of her eggs and freeze them for possible use later.

Lim was one of about 1,200 unmarried women who underwent the operation last year at CHA Medical Center. In 2019, the number of patients for the same treatment was about 600. CHA is South Korea’s largest fertility business, accounting for about 30 percent of the market.

“It’s a big relief and it gives me peace of mind to know that I have healthy eggs frozen right here,” she said.

Freezing eggs to gain reproductive time is an option increasingly explored by women worldwide. And, South Korea has one of the world’s lowest fertility rates. The average number of children born to a woman over her reproductive life in South Korea was just 0.81 last year. That compares with an average rate of 1.59 among developed countries in 2020. The countries are members of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, or OECD.

The South Korean government provides special assistance to families with children. The government budgeted $37 billion last year for policies aimed at increasing the country’s birth rate.

The low birth rate is blamed largely on South Korea’s highly competitive and costly education system. Many children are pushed into high pressure schools and private lessons from a young age.

“We hear from married couples and watch reality TV shows about how expensive it is to raise kids in terms of education costs and everything, and all these worries translate to fewer marriages and babies,” said Lim.

Housing costs have also shot up. An average apartment in Seoul, for example, costs an estimated 19 years of South Korea’s median yearly household earnings, up from 11 years in 2017.

Cho So-Young, a 32-year-old nurse at CHA who plans to freeze her eggs this coming July, is also hoping to get in a better financial position before having a child.

“If I get married now and give birth, I can’t give my baby the kind of environment I had when I grew up…I want better housing, a better neighborhood and better food to eat,” she said.

But even when finances are less of a consideration, being married is seen as required before having children in South Korea. Just two percent of births in South Korea are to unmarried parents, compared to an average of 41 percent for OECD countries.

In fact, only married women in South Korea are permitted to receive a medical fertilization process. Single women are barred under the law.

Sayuri Fujita, a Japanese celebrity based in South Korea, recently brought the issue to light. The unmarried star had to go back to Japan when she decided to get pregnant without a partner.

That needs to change, argues Jung Jae-hoon, a professor of social issues at Seoul Women’s University. She said marriages in South Korea dropped to a record low of 192,500 last year. That is down around 40 percent from ten years ago. Even when looking at marriage levels in 2019 to discount the effect of the pandemic, the drop is still a huge 27 percent.

“The least the government can do is to not get in the way of those out there who are willing” to pay the costs of having a baby, he said.

Even more worrying is the sharp drop in South Koreans’ willingness to have children at all.

A study in 2020 found that 52 percent of South Koreans in their 20s do not plan to have children when they get married. That is a massive jump from 29 percent in 2015. South Korea’s gender and family ministry carried out the study.

I’m Ashley Thompson. And I’m Caty Weaver.

Reuters reported this story. Caty Weaver adapted it for VOA Learning English.

___________________________________________________________________

Words in This Story

relief – n. removal or easing of something painful or troubling

option - n. a choice made or available

expensive - adj. costly; high in price

translate - v. to change from one form to another

median - n. a value in a series arranged from smallest to largest below and above which there are an equal number of values or which is the average of the two middle values if there is no one middle value

prerequisite - n. something that is needed before an action can progress