In November 2018, about 600 people gathered for a two-day convention in Denver, Colorado.

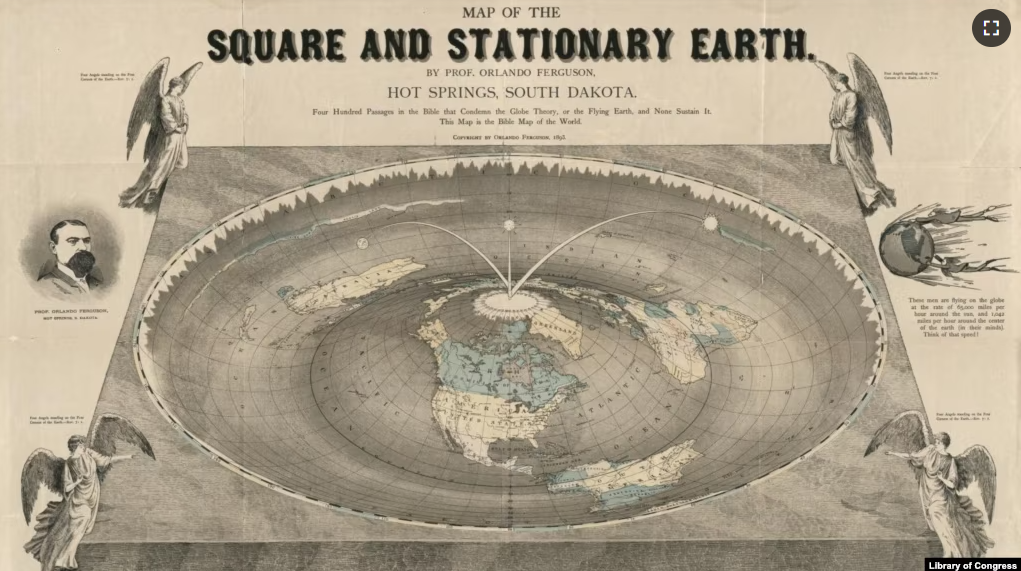

They wore clothes saying the Earth is flat. They listened to speakers who rejected findings from the American space agency NASA and much of the scientific community. They believed that the Earth is a flat, thin round object as seen in pictures taken from space.

Many pseudoscience claims are often connected to conspiracy theories. In addition to flat Earth, the Colorado Sun reported that many attendees believed that vaccines do not protect against disease. And they did not believe the Apollo moon landings, the Sandy Hook shooting, and the attack on September 11 were real.

Among the attendees at the flat Earth convention was Craig Foster. He is a professor of psychology at the State University of New York (SUNY) Cortland. He went to the convention to study the ways “flat-Earthers” think, communicate, and experience their gatherings.

Faulty reasoning

Foster now teaches a class called Psychology of Pseudoscience at SUNY Cortland. The class helps students understand why people believe in and support pseudoscience. Pseudo means not real. Pseudoscience is a collection of theories and practices mistakenly believed by supporters as being based on science.

Foster wrote in The Conversation that the class explores two issues: “motivated reasoning” and “group polarization”.

- Motivated reasoning is “the tendency for people to process information in a way that helps them confirm what they already want to believe.” For example, this can lead them to rely on only one or two examples to support their claims while ignoring other information.

- People also tend to socialize with groups of people who agree with them. Foster said that once people become involved socially and connect a belief to their identity, it becomes increasingly difficult for them to give up those beliefs, even if the claims are false.

Foster told VOA: “A big driver of the problem, the real driver, is when people are so invested they just can’t see their way out of it anymore.”

Jarrod Atchison teaches a class called Conspiracy Theories in American Public Discourse at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. He said the internet has affected the spread of false claims, and many colleges now offer classes centering on misinformation.

Atchison said conspiracy groups like Q-Anon would invite their online followers to find evidence to support a claim. Rather than relying on a few experts, conspiracy movements can now get thousands of people to join in the building of the beliefs.

Atchison told VOA: “. . .but it’s been amplified in our new media environment… It’s so much more participatory because anybody can get credibility in that community if they have a creative interpretation of what’s being put out into the world.”

Preparing students

Both Foster and Atchison train students to understand the ways promoters of pseudoscience and conspiracies think. Atchison helps students form what he calls “argument maps” which show the ways conspiracy theorists build their arguments. Once students can “read” the map, they can develop a plan to push back against the conspiracy.

In Foster’s class, students must create their own pseudoscientific claim and write a paper supporting it. One student even wrote what Foster calls a “pseudohistorical” paper, claiming that owls are intelligent aliens who have been secretly controlling humans for centuries.

Foster said there are pseudoscientific claims his students sometimes believe are true, such as astrology and creationism. Astrology is the belief that the relative position of stars influences a person’s personality and life events. Creationism denies the theory of human evolution. He said these cases force students to examine their own reasoning.

Both professors brought guest speakers to their classes, including supporters of Bigfoot – an ape-like creature two-and-a-half meters tall believed to live in the northwestern U.S. and Canada.

Foster wants his students to understand that believers in Bigfoot, ghosts, or psychics are not “crazy” or unintelligent. He added that arguing with these believers rarely changes their views. And students need to learn how to communicate respectfully with people whose beliefs may differ from their own.

Foster’s class also looked at the danger of the anti-vaccination movements, investments run by psychics, and denial of climate change.

And Atchison talked about an exercise from the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) last year. The exercise imagined an asteroid hitting Winston-Salem, home to about 250,000 people.

Atchison said: “And they (FEMA) came to the conclusion that 20 percent of Winston-Salem would not evacuate because they would not trust the message. They would not trust NASA and they would not trust FEMA”

He said, “NASA and FEMA… are starting to ask the same question: with science as politicized as it is today, how do we talk about this stuff in a way that could persuade people when their lives might depend on it?”

I’m Andrew Smith. And I’m Jill Robbins.

Andrew Smith wrote this story for VOA Learning English.

Quiz – University Classes on Pseudoscience, Conspiracies

Start the Quiz to find out

____________________________________________________________________

Words in This Story

conspiracy -n. secret planning by a group of people to do something harmful or illegal

motivated -adj. showing a strong desire to achieve a certain goal or result

polarization -n. division into two opposing groups or forces

tendency -n. a recurring habit or inclination to act or occur in a certain way

amplify -v. to increase in intensity or force

participatory -adj. characterized by active inclusion and participation of all the members of a group

interpretation -n. one’s opinion about what something means

aliens -n. intelligent life from other planets

evolution -n. the development and differentiation of forms of life (species) over time; the theory explaining such development and differentiation

psychics -n. people who claim to predict the future or communicate with the spirits of people no longer alive

evacuate -v. to move away from an area of danger

stuff -n. things, issues, or ideas