(Music)

VOICE ONE:

THE MAKING OF A NATION — a program in Special English.

(Music)

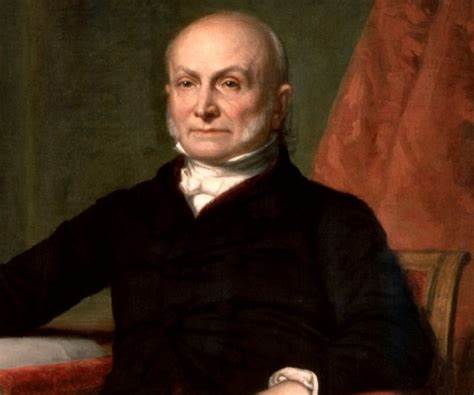

John Quincy Adams was sworn in as President of the United States on March fourth, eighteen-twenty-five. A big crowd came to the capitol building for the ceremony. All the leaders of government were there: Senators; Congressmen; the Supreme Court; and James Monroe, whose term as president was ending.

VOICE TWO:

John Quincy Adams spoke to the crowd. The main idea in his speech was unity. Adams said the Constitution and the representative democracy of the United States had proved a success. The nation was free and strong. And it stretched from the Atlantic Ocean across the continent of North America to the Pacific Ocean. During the past ten years, he noted, political party differences had eased. So now, he said, it was time for the people to settle their differences to make a truly national government. Adams closed his speech by recognizing that he was a minority president. He said he needed the help of everyone in the years to come. Then he took the oath that made him the sixth President of the United States.

VOICE ONE:

John Quincy Adams had been raised to serve his country. His father was John Adams, the second President of the United States. His mother, Abigail, made sure he received an excellent education. There were three major periods in John Quincy Adams’s public life. The period as President was the shortest. For about twenty-five years, Adams held mostly appointed jobs. He was the United States ambassador to the Netherlands, Germany, Russia, and Britain. He helped lead the negotiations that ended the War of 1812 between Britain and the United States. And he served eight years as Secretary of State. He was President for four years after that. Then he served about seventeen years in the House of Representatives. He died in eighteen-forty-eight.

VOICE TWO:

As Secretary of State, Adams had two major successes. He was mostly responsible for the policy called the Monroe Doctrine. In that policy, President James Monroe declared that no European power should try to establish a colony anywhere in the Americas. Any attempt to do so would be considered a threat to the peace and safety of the United States. Adams’s other success was the Transcontinental Treaty with Spain. In that treaty, Spain recognized American control over Florida. Spain also agreed on the line marking the western American frontier. The line went from the Gulf of Mexico to the Rocky Mountains. From there, it went to the Pacific Ocean, along what is now the border between the states of Oregon and California.

VOICE ONE:

John Quincy Adams did not care for political battles. Instead, he tried to bring his political opponents and the different parts of the country together in his cabinet. His opponents, however, refused to serve. And, although his cabinet included southerners, he did not really have the support of the south. Others in his administration tried to use the political power that he refused to use. One was Vice President John C. Calhoun of South Carolina. Calhoun hoped to be president himself one day. He tried to influence Adams’s choices for cabinet positions. Adams rejected Calhoun’s ideas and made his own choices. Senator James Barbour, a former Governor of Virginia, became Secretary of War. Richard Rush of Pennsylvania became Secretary of the Treasury. And William Wirt of Maryland continued as Attorney General. Adams thought he had chosen men who would represent the different interests of the different parts of the country.

VOICE TWO:

In his first message to Congress, President Adams described his ideas about the national government. The chief purpose of the government, he said, was to improve the lives of the people it governed. To do this, he offered a national program of building roads and canals. He also proposed a national university and a national scientific center. Adams said Congress should not be limited only to making laws to improve the nation’s economic life. He said it should make laws to improve the arts and sciences, too. Many people of the west and south did not believe that the Constitution gave the national government the power to do all these things. They believed that these powers belonged to the states. Their representatives in Congress rejected Adams’s proposals.

VOICE ONE:

The political picture in the United States began to change during the administration of John Quincy Adams. His opponents won control of both houses of Congress in the elections of eighteen-twenty-six. These men called themselves Democrats. They supported General Andrew Jackson for president in the next presidential election in eighteen-twenty-eight.

VOICE Two:

A major piece of legislation during President Adams’s term involved import taxes. A number of western states wanted taxes on industrial goods imported from other countries. The purpose was to protect their own industries. Southern states opposed import taxes. They produced no industrial goods that needed protection. And they said the Constitution did not give the national government the right to approve such taxes. Democrats needed the support of both the west and south to get Andrew Jackson elected president. So they proposed a bill that appeared to help the west, but was sure to be defeated. They thought the west would be happy that Democrats had tried to help. And the south would be happy that there would be no import taxes.

VOICE ONE:

To the Democrats’ surprise, many congressmen from the northeast joined with congressmen from the west to vote for the bill. They did so even though the bill would harm industries in the northeast. Their goal was to keep alive the idea of protective trade taxes. The bill passed in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. This left President Adams with a difficult decision. Should he sign it into law. Or should he veto it. If he signed the bill, it would show he believed that the Constitution permitted protective trade taxes. That would create even more opposition to him in the south. If he vetoed it, then he would lose support in the west and northeast. Adams signed the bill. But he made clear that Congress was fully responsible for it.

VOICE TWO:

There were other attempts by Democrats in Congress to weaken support for President Adams. For example, they claimed that Adams was mis-using government money. They tried to show that he, and his father before him, had become rich from government service. Others accused him of giving government jobs to his supporters. This charge was false. Top administration officials had urged Adams to give government jobs only to men who were loyal to him. Adams refused. He felt that as long as a government worker had done nothing wrong, he should continue in his job. During his four years as president, he removed only twelve people from government jobs. In each case, the person had failed to do his work or had done something criminal. Adams often gave jobs to people who did not support him politically. He believed it was completely wrong to give a person a job for political reasons. Many of Adams’s supporters, who had worked hard to get him elected, could not understand this. Their support for him cooled.

VOICE ONE:

The political battle between Adams’s Republican Party and Jackson’s Democratic Party was bitter. Perhaps the worst fighting took place in the press. Each side had its own newspaper. The “Daily National Journal” supported the administration. The “United States Telegraph” supported Andrew Jackson. At first, the administration’s newspaper called for national unity and an end to personal politics. Then it changed its policy. The paper had to defend charges of political wrong-doing within the Republican Party. It needed to turn readers away from these problems. So it printed a pamphlet that had been used against Andrew Jackson during an election campaign. The pamphlet accused Jackson of many bad things. The most damaging part said he had taken another man’s wife. That will be our story on the next program of THE MAKING OF A NATION.

(Music)

VOICE TWO:

You have been listening to the Special English program, THE MAKING OF A NATION. Your narrators were Steve Ember and Shirley Griffith. Our program was written by Frank Beardsley.