(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

THE MAKING OF A NATION — a program in Special English.

(MUSIC)

Once more, in the year eighteen-forty-three, Texas had become a major issue in American politics. President John Tyler wanted to make it a state in the Union. But his secretary of state, Daniel Webster, was cool toward the idea. Webster was a northerner and was opposed to having another slave state in the Union.

Tyler needed Webster’s political support and therefore did not push the issue. Then, Webster resigned. And the president appointed a southern supporter, Abel Upshur, as secretary of state. Four months after taking the job, Upshur began negotiations to bring Texas into the union. A few weeks before these negotiations were completed, Upshur was killed in an accident.

Tyler was a Whig. But he made a Democrat — John C. Calhoun — his secretary of state. He did so for two reasons. Calhoun also wanted Texas in the Union. And Tyler, although he was a Whig, hoped that Calhoun might be able to get him nominated in eighteen-forty-four as the presidential candidate of the Democratic Party.

VOICE TWO:

Calhoun completed the talks that Upshur had begun. And the treaty with Texas was signed April twelfth, eighteen-forty-four. A few days later, a letter from Calhoun to the British minister in Washington was made public. The letter was Calhoun’s answer to a British note saying that Britain wished to end slavery wherever it existed.

Calhoun defended slavery in the American south. He said that what was called slavery was really a political institution necessary for the peace, safety, and economic strength of those states where it existed. Calhoun said that statehood for Texas was necessary to the peace and security of the United States. He said that ending slavery in Texas would be a danger to the American south and to the Union itself.

VOICE ONE:

Calhoun made it seem that the United States wanted Texas — not because of some great national interest — but only to protect slavery in the south. The letter created great opposition to Texas statehood in the north. People called on their senators to vote against the acceptance of Texas. President Tyler sent the treaty with Texas to the Senate on April twenty-second, eighteen-forty-four.

This was just nine days before the Whig party opened its national convention in Baltimore. Everybody was sure that the Whigs would choose Senator Henry Clay as their presidential candidate. Clay had been working hard for the nomination for more than two years. The Democrats were to hold their convention a month later. Former President Martin Van Buren was the choice of most Democrats.

VOICE TWO:

Both Clay and Van Buren opposed statehood for Texas. Clay said it would lead to war with Mexico. Van Buren agreed. As expected, Clay was chosen as the Whig Party’s candidate for president. But Van Buren was given a surprise. The Democrats adopted a rule that their candidate must receive at least two-thirds of the votes…one-hundred and seventy-seven of the two-hundred and sixty-six delegates to the convention. Van Buren won a majority of the votes…one-hundred and forty-six. But that was not enough.

The convention voted again. But Van Buren still fell short of the necessary two-thirds. The delegates voted again and again without giving Van Buren the number he needed. After a time, Van Buren began to lose votes. None of the names nominated seemed able to win the necessary two-thirds. At last, another name was proposed: James K. Polk. Polk was at one time governor of Tennessee and Speaker of the House of Representatives. He was a supporter of statehood for Texas.

VOICE ONE:

The convention delegates voted for the eighth time. Polk got only forty-four votes. Then they voted again. This time, polk received all two-hundred sixty-six votes. Senator Silas Wright of New York was chosen as candidate for the vice-presidency. But he refused to accept, because he did not support making Texas a state. The Democrats then chose Senator George Dallas of Pennsylvania. Two other parties offered candidates in the eighteen-forty-four elections. President Tyler formed a party of his supporters and government workers. They met and nominated him for president. A fourth group, the Liberty Party, was organized by northeastern Abolitionists after the Democratic and Whig parties refused to oppose slavery. Representatives from six states met at Albany, New York. They chose James Birney for president.

VOICE TWO:

Texas was the chief issue of the eighteen-forty-four campaign. President Tyler had sent the treaty with Texas to the Senate for approval. The Senate received it just one week after the democratic convention. Those senators who had supported Martin Van Buren were still bitter over the party’s failure to nominate him as its candidate. They joined with the Whigs to defeat the treaty: thirty-five to sixteen.

Tyler still hoped to get statehood for Texas. James K. Polk, the Democratic candidate, also campaigned on promises to get Texas for the United States. The Whig candidate, Henry Clay, at first opposed statehood for Texas. But this position began to cost him support in the south. Then he said statehood might be possible if most of the people wanted it. This satisfied the slave owners of the south who wanted Texas in the Union as a slave state.

Clay angered many people in the north because he softened his opposition to Texas. Some of these began supporting the Liberty Party candidate, James Birney. The Democrats were able to get President Tyler to withdraw as a candidate. They told him that he would take votes from the Democrats and might make Clay president.

Wild campaign charges were made against both Polk and Clay. Clay was called a gambler, a duelist, a man of dishonest deals. Stories were told about Clay’s use of strong language and his love of card games. Whig newspapers reported that a traveler saw a group of slaves being sold in Tennessee. Burned into the skin of each of the slaves, the papers said, were the letters j-k-p. The initials of James K. Polk.

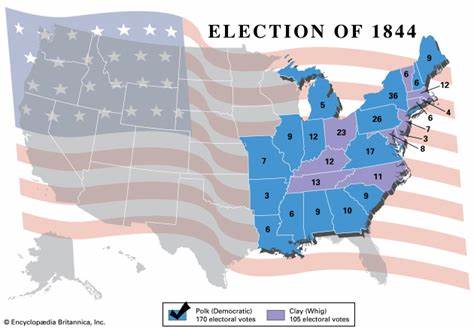

The election was very close. Two-million seven-hundred-thousand people voted. Polk received only thirty-eight-thousand votes more than Clay. But Polk got one-hundred-seventy electoral votes. Clay got only one-hundred-five.

VOICE ONE:

The election was really decided in New York state. Clay lost the state’s thirty-six electoral votes. But he did so by just fifty-one-hundred votes. He might have won the state had not James Birney received more than fifteen-thousand votes in New York.

President Tyler believed Polk’s victory showed that the American people wanted statehood for Texas. But he knew that he could never get the Senate’s approval of a Texas statehood treaty. It would take two-thirds of the Senate vote to do so. So Tyler proposed other action to make Texas a state. When Congress met in December, he proposed that Texas be given statehood through a joint resolution by both the House and Senate. Such a resolution needed only a simple majority for approval.

A resolution calling for the annexation of Texas was passed by the house in January, eighteen-forty-five, and by the Senate on February twenty-seventh. Tyler signed the bill on March first…just three days before he stepped down as president.

VOICE TWO:

The resolution invited Texas to join the Union as a state. It gave Texas the right to split itself into as many as four more states when its population was large enough. Texas could keep its public lands. But it had to pay its own debts. And Texas could enter the Union as a slave state.

The Mexican minister to Washington protested the resolution. He called it an act of aggression against his country. He demanded his passport and returned to Mexico. Britain and France tried to prevent Texas from becoming a state. They got Mexico to agree to recognize Texas independence, but only if Texas would not join the United States.

VOICE ONE:

Texas thus had two choices. It could become a state in the United States. Or it could continue as a republic with its independence recognized by Mexico. The Texas Congress chose statehood. President Polk looked even farther to the west for more new territory.

That will be our story in the next program of THE MAKING OF A NATION.

(MUSIC)

VOICE TWO:

You have been listening to the Special English program, THE MAKING OF A NATION. Your narrators were Stuart Spencer and Maurice Joyce. Our program was written by Frank Beardsley.