(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

THE MAKING OF A NATION — a program in Special English.

(MUSIC)

In any war, an important target is the enemy’s capital city. To capture the enemy’s capital usually means victory.

In America’s Civil War, the north hoped for a quick victory by capturing the southern capital at Richmond, Virginia. Northern forces were strong enough. There were about one-hundred-fifty-thousand Union soldiers in and around Washington.

General George McClellan led this army of the Potomac. His was the biggest, best-trained, and best-equipped of the Union armies.

I’m Tony Riggs. Today, Larry West and I report on Mcclellan’s move against Richmond.

VOICE TWO:

For the first year of the Civil War, the army of the Potomac did not fight. General McClellan kept making excuses for his failure to act. He had a plan, he said. And he would not move until he was sure his men were ready.

McClellan’s plan was to put his army on boats in the Potomac River. They would sail down the river to where it emptied into the Chesapeake Bay. Then he would land the boats on the coast of Virginia, east of Richmond.

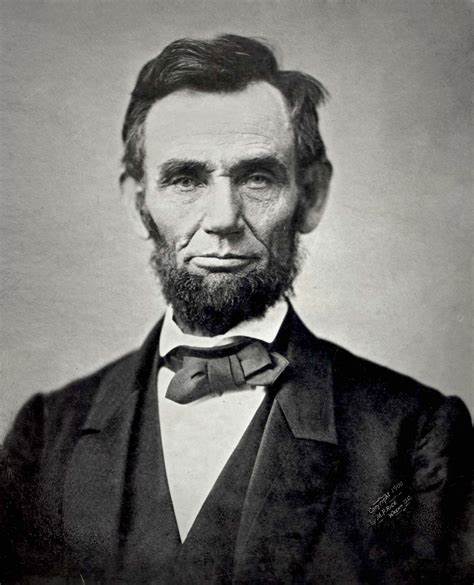

President Abraham Lincoln wanted to capture the Confederate capital. But he did not like the idea of moving all of McClellan’s men. That would leave the city of Washington without protection.

McClellan tried to calm Lincoln’s fears. He said that as soon as he marched toward Richmond, any Confederate soldiers near Washington would withdraw. They would be needed to defend their own capital.

VOICE ONE:

The army of the Potomac began to move on March seventeenth, eighteen-sixty-two. Within two weeks, more than fifty-thousand had reached Fort Monroe, southeast of Richmond. They were equipped with one-hundred big guns and tons of supplies. Day by day, the Union force at Fort Monroe grew larger.

McClellan had planned to move quickly to Yorktown, then push on to Richmond. He would move along the finger of land between the York River and the James River.

He soon learned, however, that he could not move as quickly as planned. Heavy spring rains had turned the dirt roads into rivers of mud. McClellan’s men could push through. But there was no way they could bring their big guns. McClellan decided to wait. He did not want to attack Yorktown without artillery.

VOICE TWO:

President Lincoln was not pleased. He sent a message to McClellan. “You must strike a blow,” Lincoln said. “You must act.” But still McClellan delayed.

By the time his artillery had arrived and was in place, Confederate troops had withdrawn. They moved to the woods outside Williamsburg. McClellan chased them. For the first time, his army went into battle.

The fighting was strange. The woods were so thick that the two sides could not often see each other. Soldiers fired at the flash of gunpowder, at noises, anything that moved. Their aim was good enough. About four-thousand soldiers were killed.

VOICE ONE:

In his reports to Washington, McClellan claimed great victories at Yorktown and Williamsburg. Yet he was worried. He believed the Confederate force around Richmond was much larger than his. He demanded more men.

The Confederate force was, in fact, much smaller than the Union force. But it was deployed in a way to make it seem much larger.

The trick fooled McClellan. By the middle of May, eighteen-sixty-two, his army was only fifteen kilometers from Richmond. Still, he did not attack. He continued to wait for more men and equipment.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis was worried. He knew the Confederate army was smaller than the Union army. Davis’ military adviser, General Robert E. Lee, offered a plan.

Lee proposed that General Stonewall Jackson lead his army up Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. The north would see the move as a threat to Washington. Union troops would be kept near Washington, instead of being sent to Richmond. President Davis agreed. Orders were sent to Jackson.

VOICE TWO:

Stonewall Jackson was one of the south’s best generals. He was a forceful leader. And he could make his men march until they dropped.

He got the name “Stonewall” at the battle of Bull Run in the summer of eighteen-sixty-one. Southern soldiers were withdrawing. A Confederate officer tried to stop them. He urged them to follow Jackson’s example, to stand and fight. He shouted, “There stands Jackson — like a stone wall.”

General Jackson faced three large Union forces in and around the Shenandoah Valley. Yet he struck hard and fast, and soon had control of the valley’s main towns.

His campaign is still studied at military schools around the world. It is considered an excellent example of how to move troops quickly to where they are most needed.

VOICE ONE:

Jackson’s raids produced the exact effect Robert E. Lee had wanted.

Everyone in Washington feared an immediate attack on the city. Soldiers were hurried to the capital from Baltimore and other nearby cities. And President Lincoln sent thousands of troops to chase Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley, instead of helping McClellan at Richmond.

The Union army outside Richmond was deployed on either side of the Chickahominy River. The Chickahominy was not a big river. It could be crossed easily at several places.

While McClellan waited to attack the Confederate capital, heavy rains began to fall. The little river began to rise. The commander of Confederate forces in Richmond saw this as a chance to smash a large part of McClellan’s army.

VOICE TWO:

The flooding river would soon cut the Union force completely in two. When that happened, the Confederates would attack. They expected to destroy at least half of McClellan’s army.

The plan seemed good. And after the first few hours of battle, the Confederates were close to victory. But one bridge remained over the Chickahominy River. Union soldiers were able to cross it. The Confederates were forced to withdraw to their earlier positions.

No ground was gained. And more than eleven-thousand men were killed or wounded. Among the wounded was the commander of all Confederate forces, General Joe Johnston. General Robert E. Lee would take his place.

VOICE ONE:

Lee wasted no time. He wanted to push the Union army far away from Richmond. First, however, he wanted more information about his enemy. He sent a young officer — Jeb Stuart — to get it.

Stuart set off with more than a thousand men on horseback. Theirs was a wild ride around the edge of the Union army. When they reported back three days later, General Lee knew exactly where he would attack.

It would be the first in a series of battles known as the Seven Days Campaign.

VOICE TWO:

Lee took a big chance. He moved most of his men into position to attack what he now knew was the weak, right side of the Union line. He left only a few thousand men to defend Richmond.

He hoped the Union commander, McClellan, would be fooled by this plan. For if McClellan discovered how few men were left behind, he could smash through easily and capture the city.

With the help of Stonewall Jackson’s army, Lee’s plan worked. McClellan was fooled. And after a day of fierce fighting, he was forced to withdraw from the area.

VOICE ONE:

Lee chased McClellan for a while. They clashed at such places as Mechanicsville, White Oak Swamp, and finally Malvern Hill. The south won the Seven Days Campaign. The threat to Richmond was ended. The Confederacy was saved.

But victory came at a terrible price. Twenty-thousand Confederate soldiers were killed or wounded. As both the north and south were learning quickly, the Civil War was becoming more costly than anyone had imagined.

(MUSIC)

VOICE TWO:

You have been listening to the Special English program, THE MAKING OF A NATION. Your narrators were Tony Riggs and Larry West. Our program was written by Frank Beardsley.