(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

THE MAKING OF A NATION — a program in Special English.

(MUSIC)

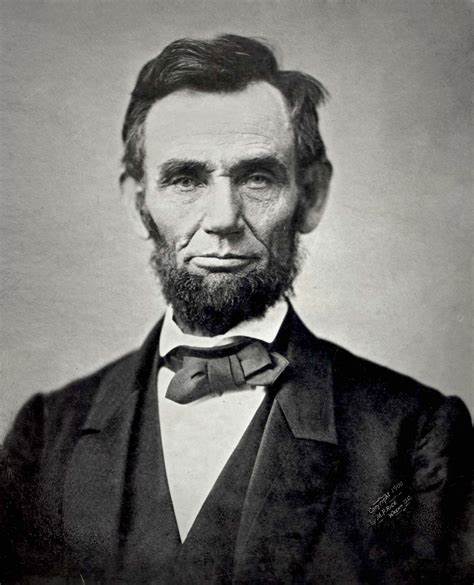

America’s Civil War of the eighteen-sixties began as a struggle over a state’s right to leave the Union. President Abraham Lincoln firmly believed that a state did not have that right. And he declared war on the southern states that did leave.

Lincoln had one and only one reason to fight: to save the Union. In time, however, there was another reason to fight: to free the Negro slaves.

I’m Harry Monroe. Today, Kay Gallant and I continue the story of how president Lincoln dealt with this issue.

VOICE TWO:

Lincoln had tried to keep the issue of slavery out of the war. He feared it would weaken the northern war effort. Many men throughout the north would fight to save the Union. They would not fight to free the slaves.

Lincoln also needed the support of the four slave states that had not left the Union: Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri. He could not be sure of their support if he declared that the purpose of the war was to free the slaves.

Lincoln was able to follow this policy, at first. But the war to save the Union was going badly. The north had not won a decisive victory in Virginia, the heart of the Confederacy.

To guarantee continued support for the war, Lincoln was forced to recognize that the issue of slavery was, in fact, a major issue. And on September twenty-second, eighteen-sixty-two, he announced a new policy on slavery in the rebel southern states. His announcement became known as the Emancipation Proclamation.

VOICE ONE:

American newspapers printed the proclamation. This is what it said:

“I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States and Commander-in-Chief of the army and navy, do hereby declare that on the first day of January, eighteen-sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any state then in rebellion against the United States, shall then become and be forever free.

“The government of the United States, including the military and naval forces, will recognize and protect the freedom of such persons, and will interfere in no way with any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.”

For political reasons, the proclamation did not free slaves in the states that supported the Union. Nor did it free slaves in the areas around Norfolk, Virginia, and New Orleans, Louisiana.

VOICE TWO:

Most anti-slavery leaders praised the Emancipation Proclamation. They had waited a long time for such a document.

But some did not like it. They said it did not go far enough. It did not free all of the slaves in the United States…only those held by the rebels.

Lincoln answered that the Emancipation Proclamation was a military measure. He said he made it under his wartime powers as Commander-in-Chief. As such, it was legal only in enemy territory.

Lincoln agreed that all slaves should be freed. It was his personal opinion. But he did not believe that the Constitution gave him the power to free all the slaves. He hoped that could be done slowly, during peacetime.

VOICE ONE:

Lincoln’s new policy on slavery was welcomed warmly by the people of Europe. It won special praise in Britain.

The British people were deeply concerned about the Civil War in America. The United States navy had blocked southern exports of cotton. The British textile industry — which depended on this cotton — was almost dead. Factories were closed. Hundreds of thousands of people were out of work.

The British government watched and worried as the war continued month after month. Finally, late in the summer of eighteen-sixty-two, British leaders said the time had come for them to intervene. They would try to help settle the American dispute.

Britain would propose a peace agreement based on northern recognition of southern rights. If the north rejected the agreement, Britain would recognize the Confederacy.

VOICE TWO:

Then came the news that President Lincoln was freeing the slaves of the south. Suddenly, the Civil War was a different war.

No longer was it a struggle over southern rights. Now it was a struggle for human freedom.

The British people strongly opposed slavery. When they heard that the slaves would be freed, they gave their support immediately to President Lincoln and the north. Britain’s peace proposals were never offered.

The Emancipation Proclamation had cost the south the recognition of Britain and France.

VOICE ONE:

The south was furious over the proclamation. Southern newspapers attacked Lincoln. They accused him of trying to create a slave rebellion in states he could not occupy with troops. They also said the proclamation was an invitation for Negroes to murder whites.

The Confederate Congress debated several resolutions to fight Lincoln’s proclamation.

One resolution would make slaves of all Negro soldiers captured from the Union army. Another called for the execution of white officers who led black troops. Some southern lawmakers even proposed the death sentence for anyone who spoke against slavery.

VOICE TWO:

In the north, most people cheered the new policy on slaves. Some, however, opposed it. They said the policy would cause the slave states of the Union to secede. Those states would join the Confederacy. Or, they said, it would cause freed slaves to move north and take away jobs from whites.

There also was another reason. Eighteen-sixty-two was a congressional election year. The Democratic Party was the opposition party at that time. Party leaders believed their candidates would have a better chance of winning if they opposed the policy.

Democrats said the policy was proof that anti-slavery extremists were in control of the government.

VOICE ONE:

As we said, Abraham Lincoln announced the Emancipation Proclamation on September twenty-second, eighteen-sixty-two. But Lincoln said he would not sign the proclamation until the first day of eighteen-sixty-three.

That gave the southern states one-hundred days to end their rebellion…or face the destruction of slavery.

VOICE TWO:

Some people thought Lincoln would withdraw the proclamation at the last minute. They did not believe he would sign a measure that was so extreme. They said the new policy would only make the south fight harder. And, as a result, the Civil War would last longer.

Others charged that the proclamation was illegal. They said the Constitution did not give the president the power to violate the property rights of citizens.

VOICE ONE:

Lincoln answered the charges.

He said: “I think the Constitution gives the Commander-in-Chief special powers under the laws of war. The most that can be said — if so much — is that slaves are property. Is there any question that, by the laws of war, property — both of enemies and friends — may be taken when needed.”

VOICE TWO:

Just before the first of the year, a congressman asked the president if he still planned to sign the Emancipation Proclamation.

VOICE ONE:

“My mind is made up,” Lincoln answered. “It must be done. I am driven to it. There is no other way out of our troubles. But although my duty is clear, it is in some way painful. I hope that the people will understand that I act not in anger. . . But in expectation of a greater good.”

VOICE TWO:

The morning of New Year’s Day was a busy time for Lincoln. It was a tradition to open the White House on that day so the president could wish visitors a happy new year.

After the last visitor had gone, Lincoln went to his office. He started to sign the Emancipation Proclamation. Then he stopped. He said:

VOICE ONE:

“I never, in all my life, felt more sure that I was doing right than I do in signing this paper. But I have been shaking hands all day, until my arm is tired. When people examine this document, they will say, ‘he was not sure about that’. But anyway, it is going to be done.”

VOICE TWO:

With those words, he wrote his name at the bottom of the paper. He had issued one of the greatest documents in American history. We will continue our story of the Civil War next week.

(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

You have been listening to the Special English program, THE MAKING OF A NATION. Your narrators were Harry Monroe and Kay Gallant. Our program was written by Frank Beardsley.

THE MAKING OF A NATION is an American history series written with English learners in mind. Developed as a radio show, each weekly program is 15 minutes long. The series begins in prehistoric times and currently ends with the presidential election of 2000.

Both the text and sound of each week’s program can be downloaded from WWW.VOA-STORY.COM. Past shows can also be found on the site.

There are more than 200 programs in the complete series, which starts over again every five years. Most of the shows were produced a long time ago. This explains why a few words here and there may sound a little dated. In fact, the series has even outlived some of the announcers. But we know from our audience that THE MAKING OF A NATION is the most popular of the feature programs in VOA Special English.

VOA Special English is a radio, TV and Internet service of the Voice of America. Programs are written with a limited vocabulary and are read at a slower speed. The purpose is to help people improve their American English as they learn about news and other subjects.