(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

THE MAKING OF A NATION — a program in Special English.

(MUSIC)

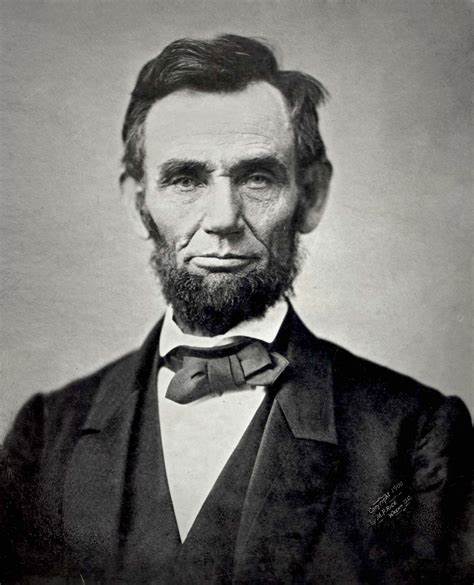

On April ninth, eighteen sixty-five, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered his army to Union General Ulysses Grant. Within weeks, America’s Civil War would be over. When people in Washington learned of Lee’s surrender, they hurried to the White House. They wanted to hear from President Abraham Lincoln. The crowd did not know that it would be one of his last speeches.

I’m Harry Monroe. Today, Kay Gallant and I tell the story of that tragic spring.

VOICE TWO:

President Lincoln spoke several days after General Lee’s surrender. The people expected a victory speech. But Lincoln gave them something else.

Already, he was moving forward from victory to the difficult times ahead. The southern rebellion was over. Now, he faced the task of re-building the Union. Lincoln did not want to punish the south. He wanted to re-join the ties that the Civil War had broken. So, when the people of the north expected a speech of victory, he gave them a speech of reconstruction, instead.

On the night of April eleventh, Lincoln appeared before a crowd outside the White House. He held a candle in one hand and his speech in the other.

VOICE ONE:

“Fellow citizens,” Lincoln said. “We meet this evening not in sorrow, but in gladness of heart. The surrender of the main army of the Confederacy gives hope of a righteous and speedy peace. The joy cannot be held back. By these recent successes, we have had pressed more closely upon us the question of reconstruction.

“We all agree,” Lincoln continued, “that the so-called seceded states are out of their correct relation with the Union. We also agree that what the government is trying to do is get these states back into their correct relation.

“I believe it is not only possible, but in fact easier to do this without deciding the legal question of whether these states have ever been out of the Union. Finding themselves safely at home, it would be of no importance whether they had ever been away.”

VOICE TWO:

There was cheering and applause when Pesident Lincoln finished, but less than when he began. The speech had been too long and too detailed to please the crowd. Lincoln, however, believed it a success. He hoped he had made the country understand one thing: the great need to forget hatred and bitterness in the difficult time of re-building that would follow the war.

The president continued to discuss his ideas on reconstruction over the next few days. On Friday, April fourteenth, he agreed to put this work aside for a while.

In the afternoon, he took his wife mary for a long drive away from the city. In the evening, they would go to the theater.

VOICE ONE:

One of the popular plays of the time, called “Our American Cousin,” was being performed at Ford’s Theater, not far from the White House. The Secretary of War did not want the Lincolns to go alone. He ordered an army officer to go with them.

The President and Misses Lincoln sat in special seats at Ford’s Theater. The presidential box was above and to one side of the stage. A guard always stood outside the door to the box. On this night, however, the guard did not remain. He left the box unprotected.

VOICE TWO:

President Lincoln settled down in his seat to enjoy the play. As he did so, a man came to the door of the box. He carried a gun in one hand and a knife in the other. The man entered the presidential box quietly. He slowly raised the gun. He aimed it at the back of Lincoln’s head. He fired.

Then the man jumped from the box to the stage three meters below. Many in the theater recognized him. He was an actor: John Wilkes Booth.

Booth broke his leg when he hit the stage floor. But he pulled himself up, shouted “Sic semper tyrannis!” — ‘Thus ever to tyrants!’ — and ran out the door. He got on a horse….and was gone.

VOICE ONE:

The attack was so quick that the audience did not know what had happened. Then a woman shouted, “The president has been shot!”

Lincoln had fallen forward in his seat, unconscious. Someone asked if it was possible to move him to the White House. A young army doctor said no. The president’s wound was terrible. He would die long before reaching the White House.

So Lincoln was moved to a house across the street from Ford’s Theater. A doctor tried to remove the bullet from the president’s head. He could not. Nothing could be done, except wait. The end was only hours away.

VOICE TWO:

Cabinet members began to arrive, while wild reports spread through the city: the Confederates had declared war again! There was fighting in the streets!

An official of the War Department described the situation. “The extent of the plot was unknown. From so horrible a beginning, what might come next. How far would the bloody work go. The safety of Washington must be looked after. The people must be told. The assassin and his helpers must be captured.”

VOICE ONE:

Early the next morning, April fifteenth, Abraham Lincoln died. A prayer was said over his body. His eyes were closed.

The news went out by telegraph to cities and towns across the country. People read the words, but could not believe them. To millions of Americans, Abraham Lincoln’s death was a personal loss. They had come to think of him as more than the President of the United States. He was a trusted friend.

People hung black cloth on their doors in sorrow. Even the south mourned for Lincoln, its former enemy. Southern General Joe Johnston said: “Mr. Lincoln was the best friend we had. His death is the worst thing that could happen for the south.”

VOICE TWO:

Messages of regret came from around the world.

British labor groups said they could never forget the things Lincoln had said about working people. Things such as: “The strongest tie of human sympathy should be one uniting all working people of all nations and tongues.”

A group representing hundreds of French students sent this message:

“In President Lincoln we mourn a fellow citizen. There are no longer any countries shut up in narrow frontiers. Our country is everywhere where there are neither masters nor slaves. Wherever people live in liberty or fight for it. We look to the other side of the

ocean to learn how a people which has known how to make itself free…knows how to preserve its freedom.”

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln touched the imagination of America’s writers. Many tried to put their feelings into words. Walt Whitman wrote several poems of mourning. Here is part of one of them, “O Captain! My Captain!”

Announcer:

Here captain! Dear father!

This arm beneath your head!

It is some dream that on the deck,

You’ve fallen cold and dead.

My captain does not answer, his lips are pale and still,

My father does not feel my arm, he has no pulse nor will.

The ship is anchor’d safe and sound, its voyage closed and done,

From fearful trip the victor ship comes in with object won;

Exult o shores, and ring o bells!

But I with mournful tread,

Walk the deck my captain lies,

Fallen cold and dead.

VOICE TWO:

Abraham Lincoln was assassinated in the spring. That is the time of year when lilac plants burst into flower throughout much of the United States. One of Walt Whitman’s most beautiful poems in honor of Lincoln is called, “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloomed.” Here is part of that poem.

Announcer:

When lilacs last in the dooryard bloom’d

And the great star early droop’d in the western sky in the night,

I mourned, and yet shall mourn with ever-returning spring.

Ever-returning spring, trinity sure to me you bring,

Lilac blooming perennial and drooping star in the west,

And thought of him I love. . .

Coffin that passes through lanes and streets,

Through day and night with the great cloud darkening the land. . .

With the countless torches lit,

Wiith the silent sea of faces and the unbared heads. . .

With the tolling, tolling bells’ perpetual clang,

here, coffin that slowly passes,

I give you my sprig of lilac.

(MUSIC)

VOICE TWO:

You have been listening to the Special English program, THE MAKING OF A NATION. Your narrators were Harry Monroe and Kay Gallant. The poems were read by Shep O’Neal. Our program was written by Harold Berman and Frank Beardsley.