(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

THE MAKING OF A NATION — a program in Special English by the Voice of America.

(MUSIC)

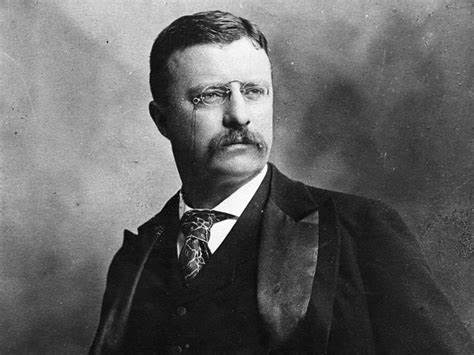

Theodore Roosevelt became President of the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century. It was a time of great technological progress in the United States. Yet many people felt there was too little social progress. They demanded reforms in politics, industry, and the use of natural resources.

Theodore Roosevelt supported the call for reforms. His first target was big business.

I’m Harry Monroe. Today, Kay Gallant and I continue the story of Roosevelt’s administration.

VOICE TWO:

In the early nineteen-hundreds, a group of wealthy American businessmen agreed to join their railroads. They formed a company, or trust, to control the joint railroad. The new company would have complete control of rail transportation in the American west. There would be no competition.

President Roosevelt believed the new company violated the Sherman Anti-Trust Law. The law said it was illegal for businesses to interfere with trade among the states. Roosevelt said he would make no compromises in enforcing the law. He asked the Supreme Court to break up the railroad trust.

“We are not,” roosevelt said, “attacking these big companies. We are only trying to do away with any evil in them. We are not hostile to them. But we believe they must be controlled to serve the public good.”

VOICE ONE:

The Supreme Court ruled against the railroad trust. In the next few years, other trusts would be broken up in the same way. The American people called this trust-busting. And they called Theodore Roosevelt the trust-buster.

Roosevelt made several speeches explaining his position on big business. Everywhere he went, he found wide public support. Later, he told a friend why people liked him so well. He said: “I put into words what is in their hearts and minds. . . But not in their mouths.”

VOICE TWO:

President Roosevelt won even more public support for his actions during a labor crisis in the coal industry. The incident was one of many in American history in which a president had to decide if he should interfere in private industry.

Coal miners went on strike in the spring of nineteen-oh-two. They demanded more pay and safer working conditions. Mine owners refused to negotiate. One even insulted the miners. He said: “The rights and interests of the laboring man will be protected and cared for. It will not be the labor activists who take care of him. It will be the Christian men to whom God in his great wisdom has given the control of the property interests of this country.”

This self-serving use of religion made many Americans support the striking workers.

VOICE ONE:

After several months, President Roosevelt invited coal mine owners and union leaders to a meeting in Washington. He asked them to keep in mind that a third group was involved in their dispute: the public. He warned that the nation faced the possibility of a winter without heating fuel.

Roosevelt said: “I did not call this meeting to discuss your claims and positions. I called it to appeal to your love of country.”

The union leaders said they were willing to have the president appoint an independent committee to settle the strike. They said they would accept the committee’s decision as final. The mine owners rejected the idea. One warned the president not even to talk about it. Such talk, he said, was illegal interference in private industry.

VOICE TWO:

That made Theodore Roosevelt angry. Later, he said: “If it were not for the high office I held, I would have taken him by the seat of the pants and the nape of the neck and thrown him out the window.”

Finally, Roosevelt got both sides to agree to a compromise. Mine owners agreed to have an independent committee study the miners’ demands. And the miners’ agreed to return to work until the study was completed.

Several months later, the report was ready. The committee proposed that miners accept a smaller pay increase in exchange for improved working conditions. Both sides accepted the proposal. The coal strike ended.

VOICE ONE:

Not everyone was happy. Many people still felt Roosevelt had no right to interfere. Roosevelt disagreed. “My business,” he said, “is to see fair play among all men — capitalists or wage-workers. All I want to do is see that every man has a fair deal. No more, no less.” Roosevelt believed the United States needed a strong leader. He planned to strengthen the presidency whenever he could.

Roosevelt was an active, noisy man. As one writer described him: “Theodore is always the center of action. When he goes to a wedding, he wants to be the bride. When he goes to a funeral, he wants to be the dead man.”

Many of Roosevelt’s friends thought he was an over-grown boy. “You must always remember,” one said, “that the president is about six years old.” Another friend sent this message to Roosevelt on his forty-sixth birthday: “you have made a very good start in life. We have great hopes for you when you grow up.”

VOICE TWO:

Theodore Roosevelt loved outdoor activities. He especially loved the natural beauty of the land. He worried about its future. Roosevelt wrote: “I recognize the right and duty of this generation to develop and use the natural riches of our land. But I do not recognize the right to waste them, nor to rob — by wasteful use — the generations that come after us.”

Roosevelt set aside large areas of forest land for national use. He created fifty special areas to protect wildlife. And he established a number of national parks.

VOICE ONE:

Theodore Roosevelt faced the responsibilities of foreign policy with the same strength he used in facing national problems. He firmly believed in expanding American power in the world. “We have no choice,” he said, “as to whether or not we will play a great part in the world. All that we can decide is whether we will play our part well or poorly.”

To play well, Roosevelt said, the United States needed a strong Navy. It also needed a canal across Central America so the Navy could sail quickly between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

VOICE TWO:

For many years, people had dreamed of such a waterway. With a canal across Central America, ships could sail directly from ocean to ocean. They would not have to make the long, costly voyage around the southern end of south America.

The most likely place to build such a canal was at the thinnest point of land: Panama. Another possible place was just to the north: Nicaragua.

Over the years, several attempts were made to build the canal.

VOICE ONE:

In the eighteen eighties, Ferdinand de Lesseps — builder of the Suez Canal — formed a French company to build a waterway across Panama. De Lesseps spent three hundred million dollars to build just one-third of the canal. He could get no more money. His company failed.

In the eighteen nineties, an American company tried to build a canal across Nicaragua. It made little progress. After three years, it gave up the attempt. When Theodore Roosevelt became president in the early nineteen hundreds, he was ready to try again.

VOICE TWO:

A study was made to decide which would be a better place for the canal — Panama or Nicaragua. Engineers said it would cost less to complete the canal De Lesseps had started twenty years earlier in Panama. But De Lesseps’ company still owned the land on which the canal would be built. The United States would have to buy the land, as well as the rights to build the waterway.

The study decided it would be less costly, overall, to build the canal in Nicaragua. The proposal went to the United States Congress for approval. That will be our story next week.

(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

You have been listening to the Special English program, THE MAKING OF A NATION. Your narrators were Harry Monroe and Kay Gallant. Our program was written by Frank Beardsley.