(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

THE MAKING OF A NATION — a program in Special English by the Voice of America.

(MUSIC)

The United States played a small part in world events during the eighteen hundreds. At the beginning of the nineteen hundreds, however, it expanded its interests throughout the world. America’s president at that time strongly supported the expansion. He was Theodore Roosevelt.

I’m Frank Oliver. Today, Shirley Griffith and I complete the story of America’s twenty-sixth president.

VOICE TWO:

Theodore Roosevelt became president in nineteen-oh-one after the assassination of President William McKinley. He completed the last three years of McKinley’s term. Then he was elected in his own right. Those four years are spoken of as Roosevelt’s second term.

It was during this second term that Roosevelt gained his most important foreign policy success. He negotiated an end to a war between Russia and Japan. Later, he was asked to settle another international dispute. At issue was Morocco.

VOICE ONE:

In nineteen-oh-four, France and Britain signed an agreement on North Africa. The agreement gave Britain control over Egypt. It gave France responsibility for security and reforms in Morocco. Germany opposed the agreement. It felt threatened by any French-British alliance. And it feared France would block German trade ties with Morocco.

Germany demanded an “open door” policy that would permit all countries to trade freely in Morocco. It proposed an international conference to settle the dispute. France and Britain rejected the idea. The ruler of Germany, Kaiser Wilhelm the Second, warned that the dispute could lead to war. The Kaiser asked Theodore Roosevelt to intervene.

VOICE TWO:

President Roosevelt agreed to help. Some American lawmakers criticized him. They said it was an American tradition not to get involved in European disputes. But Roosevelt believed peace was more important than tradition. He set up the conference in the Spanish seaport of Algeciras. Twelve European nations and the United States attended.

The conference agreed to an open door trade policy in Morocco. It organized an international bank to control Morocco’s finances. And it gave France and Spain almost complete control over police forces in Morocco’s port cities.

VOICE ONE:

Theodore Roosevelt had become a powerful world leader. At home, however, he was losing power.

One reason was an economic depression. Business leaders blamed it on Roosevelt. They said it was the result of his efforts to gain government control over industry. The other reason was one he had created himself.

At that time, there was no law limiting a president’s term in office. But America’s first president, George Washington, had established a tradition of only two terms. When Theodore Roosevelt won the election of nineteen-oh-four, he announced he would not be a candidate in nineteen-oh-eight. He had completed the term of President McKinley. He would serve a full term of his own. That was enough.

Later, he said: “I would be willing to cut off my hand if I could call back that statement.”

VOICE TWO:

During his last year in office, Roosevelt was a “lame duck” president. Everyone knew he would not be back. There was little political reason to support him.

He faced increased opposition from Congress and from his own Republican Party. His final message to Congress was extremely bitter.

President Roosevelt accused Congress and the court system of working only to help rich Americans. He called for a tax on earnings. He called for legislation to give workers a greater share of the nation’s wealth. The House of Representatives voted to reject the message. It said Roosevelt had failed to show respect for the legislative branch of government.

VOICE ONE:

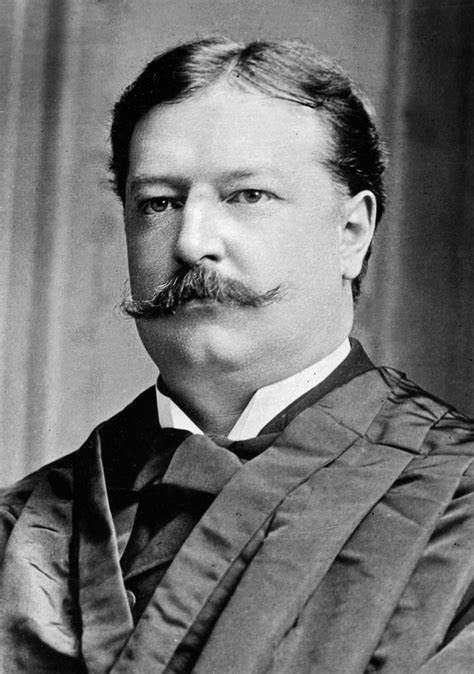

Roosevelt refused to give up hope for the policies he believed America needed. He would not be able to fight for these policies himself. But he could find a presidential candidate who would. He was sure the people would vote for his choice. He decided on his close friend, Secretary of War William Howard Taft.

Taft had spent most of his life in government service. He had been a judge in both a state court and a federal court. He had been a lawyer in the justice department. And he had been governor of the Philippines.

VOICE TWO:

There was one problem, however. Taft did not want to be president. He really wanted to be Chief Justice of the United States. But there were no immediate openings on the Supreme Court. Also, his wife, his brothers, and his good friend — Theodore Roosevelt — urged him to run. So, Taft agreed to be a candidate for the Republican presidential nomination in nineteen-oh-eight.

When he won the nomination, taft said: “Mr. Roosevelt led the way to reform. My job — if elected — will be to complete and perfect his programs.”

The Democratic Party nominated William Jennings Bryan. Bryan had been a candidate two times before, without success.

VOICE ONE:

The presidential campaign was not especially exciting. William Howard Taft did not like being on the campaign trail. He was a big, heavy man. He did not like to travel. Roosevelt urged him to campaign with more energy.

“Hit hard, old man,” Roosevelt said. “Make the people see the truth. Let them know that for all your gentleness and kindliness, there never existed a man who was a better fighter when the need arose.”

Roosevelt’s advice and strong support helped Taft win a big victory on election day.

VOICE TWO:

A few weeks after Taft was sworn-in as president, Roosevelt left on a year-long trip overseas. He spent most of the time hunting wild animals in Africa.

President Taft wrote a warm goodbye letter to his friend. He promised to do his best as president. But he admitted he could not lead as Roosevelt had done. In fact, Taft said, he was still surprised when anyone called him “Mr. President.” Each time it happened, he turned around to see if Roosevelt was there.

VOICE ONE:

There was no question that Taft’s way of leading was much different from Roosevelt’s. Taft believed a president should not interfere too deeply in the actions of Congress. He also believed a president should not claim special powers or rights. He believed in the supreme power of the law. . . even if the law did not work very well.

The progressives who had supported Roosevelt did not support Taft. They said he was too friendly with conservatives. They said he had surrendered to special interest groups. Taft, for his part, did not like progressives. He thought they were too emotional and extreme.

VOICE TWO:

Yet Taft worked hard to put into law many parts of Roosevelt’s progressive programs. He was successful in several areas.

During his administration, for example, a separate Department of Labor was established. Two Constitutional amendments won congressional approval and were sent to the states for ratification.

One amendment provided for a federal tax on earnings. The other provided for direct, popular election of senators. Taft also worked even harder than Roosevelt to break up companies, or trusts, that blocked economic competition.

VOICE ONE:

At the same time, Taft failed in several areas.

He signed legislation that lowered import taxes. Neither businessmen nor progressive Republicans liked it. He negotiated a free trade agreement with Canada. The Canadian parliament rejected it. He believed in protecting America’s wilderness areas. Yet he did not believe existing laws gave him the right to close public lands to private development. So he was seen as an enemy of conservation.

These struggles and failures made Taft’s four years as president the unhappiest of his life.

VOICE TWO:

The final blow came in an effort to reduce the powers of the Speaker of the House of Representatives. The speaker was a conservative Republican. Progressive Republicans opposed him. The issue split the party.

Theodore Roosevelt — far from home — read about the trouble. He had promised to stay out of politics. But each of the opposing groups in his party had asked for his support.

(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

You have been listening to THE MAKING OF A NATION — a program in Special English by the Voice of America. Your narrators were Frank Oliver and Shirley Griffith. Our program was written by Frank Beardsley.