VOICE ONE:

This is Rich Kleinfeldt.

VOICE TWO:

And this is Phil Murray with THE MAKING OF A NATION — a VOA Special English program about the history of the United States.

(MUSIC)

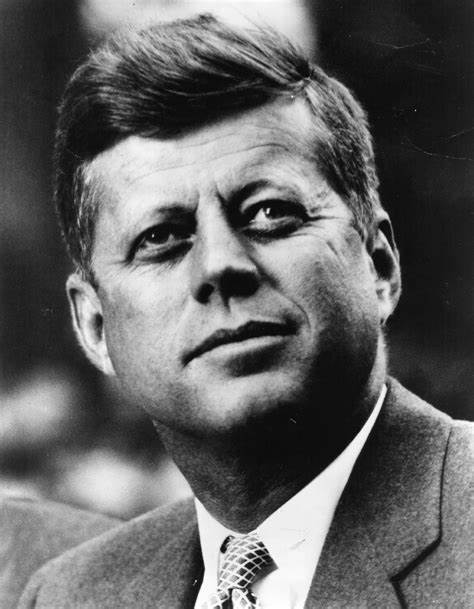

Our program today is about the beginning of the administration of President John Kennedy.

(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

January twentieth, nineteen sixty-one. John Kennedy was to be sworn-in that day as president of the United States.

It had snowed heavily the night before. Few cars were in the streets of Washington. Yet, somehow, people got to the ceremony at the Capitol building.

VOICE TWO:

The outgoing president, Dwight Eisenhower, was seventy years old. John Kennedy was just forty-three. He was the first American president born in the twentieth century.

Both Eisenhower and Kennedy served in the military in World War Two. Eisenhower served at the top. He was commander of allied forces in Europe. Kennedy was one of many young navy officers in the pacific battle area.

Eisenhower was a hero of the war and was an extremely popular man. Kennedy was extremely popular, too, especially among young people. He was a fresh face in American politics. To millions of Americans, he represented a chance for a new beginning.

VOICE ONE:

Not everyone liked John Kennedy, however. Many people thought he was too young to be president. Many opposed him because he belonged to the Roman Catholic Church. A majority of Christians in America were Protestant. There had never been a Roman Catholic president of the United States. John Kennedy would be the first.

VOICE TWO:

Dwight Eisenhower served two terms during the nineteen-fifties. That was the limit for American presidents. His vice president, Richard Nixon, ran against Kennedy in the election of nineteen-sixty.

Many Americans supported Nixon. They believed he was a stronger opponent of communism than Kennedy. Some also feared that Kennedy might give more consideration to the needs of black Americans than to white Americans.

The election of nineteen-sixty was one of the closest in American history. Kennedy defeated Nixon by fewer than one hundred-twenty thousand popular votes. Now, he would be sworn-in as the nation’s thirty-fifth president.

(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

One of the speakers at the ceremony was Robert Frost. He was perhaps America’s most popular poet at the time. Robert Frost planned to read from a long work he wrote especially for the ceremony. But he was unable to read much of it. The bright winter sun shone blindingly on the snow. The cold winter wind blew the paper in his old hands.

VOICE TWO:

John Kennedy stood to help him. Still, the poet could not continue. Those in the crowd felt concerned for the eighty-six-year-old man. Suddenly, he stopped trying to say his special poem. Instead, he began to say the words of another one, one he knew from memory. It was called “The Gift Outright.”

Here is part of that poem by Robert Frost, read by Stan Busby:

VOICE THREE:

The land was ours before we were the land’s.

She was our land more than a hundred years before we were her people …

Something we were withholding made us weak

Until we found out that it was ourselves

We were withholding from our land of living …

Such as we were we gave ourselves outright.

VOICE ONE:

Soon it was time for the new president to speak. People watching on television could see his icy breath as he stood. He was not wearing a warm coat. His head was uncovered.

Kennedy’s speech would, one day, be judged to be among the best in American history. The time of his inauguration was a time of tension and fear about nuclear weapons. The United States had nuclear weapons. Its main political enemy, the Soviet Union, had them, too. If hostilities broke out, would such terrible weapons be used?

VOICE TWO:

Kennedy spoke about the issue. He warned of the danger of what he called “the deadly atom.” He said the United States and communist nations should make serious proposals for the inspection and control of nuclear weapons. He urged both sides to explore the good in science, instead of its terrors.

KENNEDY: “Together let us explore the stars, conquer the deserts, eradicate disease, tap the ocean depths, and encourage the arts and commerce … Let both sides join in creating a new endeavor, not a new balance of power, but a new world of law, where the strong are just and the weak secure and the peace preserved.”

VOICE ONE:

Kennedy also spoke about a torch — a light of leadership being passed from older Americans to younger Americans. He urged the young to take the torch and accept responsibility for the future. He also urged other countries to work with the United States to create a better world.

KENNEDY: “The energy, the faith, the devotion which we bring to this endeavor will light our country and all who serve it — and the glow from that fire can truly light the world. And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country. My fellow citizens of the world: Ask not what America will do for you, but what together we can do for the freedom of man.”

(MUSIC)

VOICE TWO:

John Kennedy’s first one hundred days as president were busy ones.

He was in office less than two weeks when the Soviet Union freed two American airmen. The Soviets had shot down their spy plane over the Bering Sea. About sixty million people watched as Kennedy announced the airmen’s release. It was the first presidential news conference broadcast live on television in the United States. Kennedy welcomed the release as a step toward better relations with the Soviet Union.

The next month, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev made another move toward better relations. He sent Kennedy a message. The message said that disarmament would be a great joy for all people on earth.

VOICE ONE:

A few weeks later, President Kennedy announced the creation of the Peace Corps. He had talked about this program during the election campaign. The Peace Corps would send thousands of Americans to developing countries to provide technical help.

Another program, the alliance for progress, was announced soon after the peace corps was created. The purpose of the alliance for progress was to provide economic aid to Latin American nations for ten years.

VOICE TWO:

The space program was another thing Kennedy had talked about during the election campaign. He believed the United States should continue to explore outer space.

The Soviet Union had gotten there first. It launched the world’s first satellite in nineteen fifty-seven. Then, in April, nineteen sixty-one, the Soviet Union sent the first manned spacecraft into orbit around the earth.

VOICE ONE:

The worst failure of Kennedy’s administration came that same month. On April seventeenth, more than one thousand Cuban exiles landed on a beach in western Cuba. They had received training and equipment from the United States Central Intelligence Agency. They were to lead a revolution to overthrow the communist government of Cuba. The place where they landed was called Bahia de Cochinos — the Bay of Pigs.

The plan failed. Most of the exiles were killed or captured by the Cuban army.

VOICE TWO:

It had not been President Kennedy’s idea to start a revolution against Cuban leader Fidel Castro. Officials in the last administration had planned it. However, most of Kennedy’s advisers supported the idea. And he approved it.

In public, the president said he was responsible for the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion. In private, he said, “All my life I have known better than to depend on the experts. How could I have been so stupid.”

VOICE ONE:

John Kennedy’s popularity was badly damaged by what happened in Cuba. His next months in office would be a struggle to regain the support of the people. That will be our story next week.

(MUSIC)

VOICE TWO:

This program of THE MAKING OF A NATION was written by Jeri Watson and produced by Paul Thompson. This is Phil Murray.

VOICE ONE:

And this is Rich Kleinfeldt. Join us again next week for another VOA Special English program about the history of the United States.