(THEME)

VOICE ONE:

THE MAKING OF A NATION — a program in Special English by the Voice of America.

(THEME)

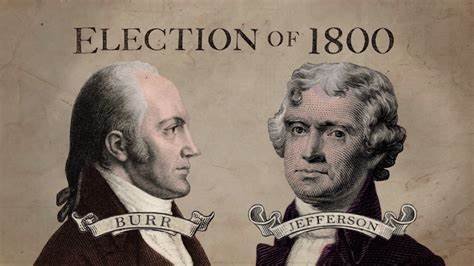

I’m Frank Oliver. Today, Shep O’Neal and I tell about America’s presidential election of Eighteen-Hundred. The two major candidates were President John Adams and Vice President Thomas Jefferson. Adams represented the Federalist Party. Jefferson represented the Republican Party.

VOICE TWO:

As president, John Adams was head of the Federalist Party. But the power of that position belonged, in fact, to former Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton.

For this and other reasons, Adams did not like Hamilton. He said: “Thomas Jefferson will be a good president, if elected. I would rather be a minister to Europe under Jefferson than to be a president controlled by Hamilton.”

Hamilton did not like Adams. He did everything he could to block Adams from becoming president again. He gave his support to another Federalist candidate, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney of South Carolina.

Under the electoral system of that time, the candidate with the most votes became president. The candidate with the second highest number of votes became vice president.

VOICE ONE:

A Federalist victory in the election of Eighteen-Hundred would not be easy. The Republicans had a very strong and popular candidate — Thomas Jefferson. So, Federalist Party leaders attempted to change the electoral system.

The Constitution said state legislatures were to choose electors to vote for president. The Federalists tried to gain control over the legislatures’ decisions.

They wanted Congress to create a special committee to rule if an elector had — or did not have — the right to vote. The committee could say if an elector’s vote should be counted or thrown away.

VOICE TWO:

The committee would have six members from the Senate and six members from the House of Representatives. The thirteenth member would be the Chief Justice of the United States. Creating such a committee violated the Constitution. Federalist leaders knew this. So, they wanted Congress to approve the committee, but keep the measure secret until after the election.

The Federalists held a majority of seats in the Senate. And the Senate voted to approve the proposal. But some Federalist members of the House of Representatives denounced it. They made many changes in the proposal. The Senate refused to accept the changes. Without agreement by both houses of Congress, the bill died.

Federalist leaders saw their hopes for an election victory begin to disappear.

VOICE ONE:

By the summer of Eighteen-Hundred, Thomas Jefferson’s Republican Party had strong leaders in every state. It had many newspapers to express party ideas. Jefferson decided to take a holiday at Monticello, his farm in Virginia.

The Republican Party leader in New York was a lawyer, Aaron Burr.

Burr had served as an officer under General George Washington during America’s war for independence from Britain. After the war, he joined the Federalist Party and was elected to the United States Senate. Later, he changed parties and became a Republican. In Eighteen-Hundred, a group of both Federalists and Republicans supported him as a candidate for president.

VOICE TWO:

Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton were bitter enemies. When Hamilton learned of a plan by his own party to elect Burr president, instead of Jefferson, his reaction was quick and sharp.

“Anybody,” he said, “even Thomas Jefferson, is better than Aaron Burr. Jefferson is not dangerous. Burr is. Jefferson’s ideas of government are wrong. But at least he is an honest man. Burr is a man without honesty and character. He will destroy America.”

VOICE ONE:

The president elected in Eighteen-Hundred would govern in a new capital city. The national government would move from Philadelphia to Washington, a newly-built city in the District of Columbia. It was on the Potomac River between the states of Maryland and Virginia.

When President Adams and his wife Abigail arrived in Washington, D.C., they found a frontier town. There were few houses or streets. Missus Adams could not believe what she saw. She wrote to her daughter:

“This is a city only because we call it a city. Our house here is very big. But the rooms are not finished. There is almost no furniture. There are not enough lamps for light.”

VOICE TWO:

A street called Pennsylvania Avenue went from the president’s house to the Capitol building where Congress would meet. On each side of the street — where buildings stand today — there were fields of mud.

This was the new federal city, the new capital of the United States. This was where the winner of the presidential election of Eighteen-Hundred would begin his term of office.

VOICE ONE:

George Washington won America’s first two presidential elections without opposition. John Adams won the third presidential election by three votes. This time, in Eighteen-Hundred, there was no clear winner.

When the electors’ votes were counted, President Adams had sixty-five votes. But Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr each had seventy-three votes. So, under the Constitution, the House of Representatives would choose between Jefferson or Burr — the candidates with the highest number of votes.

Each congressman could vote. But each state had just one vote. That vote would go to the candidate supported by a majority of congressmen from the state. A candidate had to receive a majority of the state votes to win. In Eighteen-Hundred, that was nine of the sixteen states.

VOICE TWO:

The Federalists saw the situation as their last chance to control the presidency. They had two plans. They would try to block the Congress from electing either Jefferson or Burr as president. Then they would try to find a way to put executive power in the hands of a Federalist. If that plan failed, they were prepared to elect Burr.

The Federalists tried to make people believe that Burr was working with them, against Jefferson. Burr denied this. In a letter to Jefferson, Burr wrote:

“Every Republican wants you to be president of the United States. Every good Republican wants to serve under you. I would be happy and honored to be your vice president. And, if you believe I could help you better in some other position, I would do so.”

VOICE ONE:

On February eleventh, the House of Representatives began to count votes, state by state. Eight states chose Jefferson. Six chose Burr. The representatives of two states — Maryland and Vermont — gave each man an equal number of votes. There was no majority within those states. So neither man won the votes of those states.

The voting continued. All that day and throughout the night the representatives voted. Twenty-seven times the count remained the same: Eight states for Jefferson. Six for Burr. Two undecided.

The next morning, the representatives decided to rest for four hours. The voting began again at noon. There was no change.

The thirteenth of February passed, then the fourteenth and fifteenth. Still, no change. The House voted thirty-three times. It could not elect a president.

VOICE TWO:

A change in the vote of just one congressman from Maryland or Vermont could decide the contest.

Later, after the election, the representative from Delaware said he had met with two congressmen from Maryland and one from Vermont. All were Federalists. All had voted for Aaron Burr.

The Delaware congressman said they claimed they spoke with a friend of Thomas Jefferson. He said they told Jefferson’s friend they would change their votes, if Jefferson made certain promises.

Jefferson denied that he had made any political promises. He said many men tried to get promises from him. But he said he told them all that he would never become president with his hands tied.

VOICE ONE:

History experts do not agree on what really happened. What is sure is that the House of Representatives voted for the thirty-sixth time on February seventeenth. Ten states, including Maryland and Vermont, voted for Thomas Jefferson. Four states voted for Aaron Burr.

Two states — Delaware and South Carolina — did not vote. But Jefferson had the majority he needed. He would be the new president.

(THEME)

VOICE TWO:

You have been listening to the Special English program, THE MAKING OF A NATION. Your narrators were Frank Oliver and Shep O’Neal. Our program was written by Harold Braverman and Christine Johnson.