(Theme)

VOICE ONE:

THE MAKING OF A NATION — a program in Special English.

(Theme)

As we reported earlier, the United States and Britain agreed late in December, 1814, to end the war between them. The peace treaty was signed the day before Christmas at Ghent, Belgium. It took several weeks for word of the agreement to reach Washington. This resulted in two events which would not have happened had communications across the Atlantic been faster.

One of the events was the battle of New Orleans. British forces had begun the attack about the time the peace treaty was being signed in Ghent. The American commander, General Andrew Jackson, had prepared his defenses well. He won a great victory against the British in a battle that was not necessary, because the treaty had ended the war.

VOICE TWO:

The other event was a convention of New England federalists at Hartford, Connecticut. The meeting began in the middle of December and lasted through the first few days of January. Most of the representatives were from Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. There were a few from New Hampshire and Vermont. The Federalists called the meeting to protest the war with Britain. Many of them had opposed the war from the beginning. Federalist state governments refused to put their soldiers under control of the central government. And Federalist banks refused to lend to the government in Washington.

During the early part of the war, many businessmen in the New England states traded with the enemy. All these things had caused people in other parts of the country to turn against the Federalists. This, in turn, caused some Federalist extremists to talk of taking the New England states out of the union.

VOICE ONE:

There was some fear that representatives to the Hartford Convention would propose a separate and independent government for New England. Such a proposal — while the nation was at war with Britain — would seriously threaten America’s future.

Not only were the representatives at Hartford to protest the war, they also were there to plan a convention to change the United States constitution. They wanted changes that would protect the interests of the New England states. These states felt threatened because new states were being created from the western territories. These new states would weaken the power of New England. Some of the more extreme Federalists, led by Timothy Pickering, believed Britain would capture New Orleans. By doing so, Britain could control the Mississippi River, which the western states needed to move their products to market.

“If the British succeed against New Orleans,” wrote Pickering, “And I see no reason to question that they will be successful, then I shall consider the union as cut in two. I do not expect to see a single representative in the next Congress from the western states.”

VOICE TWO:

Not all the representatives at the convention were as extreme as Pickering. The majority of them were more moderate. They did not want to split the union. They only wanted to protect the interests of the New England states. These more moderate Federalists controlled the secret meetings and prevented any extreme proposals. They were able to do so because of the Republican strength in New England. True, the Federalists controlled the governments of these states, but only by small majorities. There would surely have been violence had the Federalists tried to take these states out of the union.

VOICE ONE:

The Federalist leaders made a public statement at Hartford, January fifth. They sharply criticized the war and President Madison. But they said there was no real reason to withdraw from the central government. New England’s problems, they said, resulted from the war and from the Republican government in Washington. Then the Federalists listed the changes they wanted in the constitution.

They wanted to reduce the congressional representation of the southern states, where slavery was permitted. They wanted new states added to the union only if two-thirds of Congress approved. They wished to reduce the power of the central government to interfere with trade. The Federalists wished to limit to four years the time that a man could serve as president. And they wanted only men born in the United States to serve in the government.

Three of the Federalists were chosen to take this list of proposals to Washington and give it to President Madison. By the time they arrived, Washington had received the news of the peace treaty signed at Ghent. The war was over.

VOICE TWO:

The three Federalists met with Madison. They made only small talk and said nothing about the demands of the Hartford Convention. The Federalist Party found itself greatly embarrassed by the peace. Its leaders had long denounced the war and said Britain could not be defeated. Many of them had traded with the enemy. Some had even worked with the British against their own country. They had even threatened to break up the union. While there was some question about how the war would end, the Federalist Party had supporters. But once the war was over, its supporters vanished. And the party itself soon disappeared, even in New England.

VOICE ONE:

The Senate acted quickly to approve the treaty with Britain. On February 17, 1815, President Madison declared the war officially ended. It had lasted two years and eight months. The United States had suffered 30,000 casualties — killed, wounded, or captured. But the war had united the American people. Albert Gallatin, Madison’s Treasury Secretary and one of the negotiators at Ghent, explained it this way:

“The war has renewed and reinstated the national feelings and character which the revolution had given and which were becoming weaker. The people now have more general objects of attachment with which their pride and political opinions are joined. They are more American. They feel and act more like a nation.”

VOICE TWO:

On the following Fourth of July, the nation celebrated its thirty-nineth anniversary of independence. In Washington, the man who wrote the “Star-Spangled Banner,” Francis Scott Key, spoke at the celebrations.

“My countrymen,” he said, “We hold something rich in trust for ourselves and all the rest of mankind. It is the fire of liberty. If it is ever put out, our darkened land will cast a sad shadow over the nations. If it lives, its blaze will enlighten and gladden the whole earth.”

VOICE ONE:

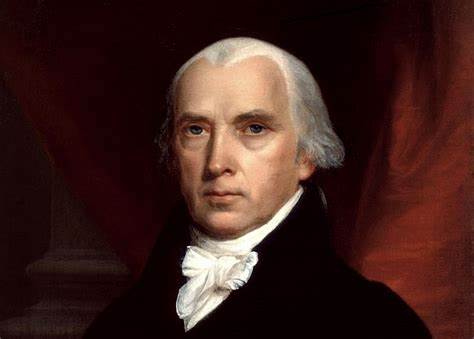

President Madison had been elected to his second term in 1812, the year the war started. The next presidential election was in 1816. Madison continued the tradition, begun by Washington and followed by Jefferson, of only serving eight years as president. Republican members of the House and Senate met March 15 to choose their presidential and vice presidential candidates. Three Republicans wanted to be president: Secretary of State James Monroe, former Senator and Secretary of War William Crawford, and New York Governor Daniel Tompkins.

Monroe received 65 votes. Fifty-four of the lawmakers voted for Crawford. With Monroe chosen as the presidential candidate, the Republicans then chose Governor Tompkins as their vice presidential candidate. The Federalists did not meet to choose a presidential candidate. But electors from three of the New England states promised to vote for a New York Federalist, Rufus King. Nineteen states voted in the elections of 1816. That will be our story next week.

(Theme)

VOICE TWO:

You have been listening to the Special English program, THE MAKING OF A NATION. Your narrators were Maurice Joyce and Jack Moyles. Our program was written by Frank Beardsley. THE MAKING OF A NATION can be heard Thursdays.