(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

THE MAKING OF A NATION — a program in Special English.

(MUSIC)

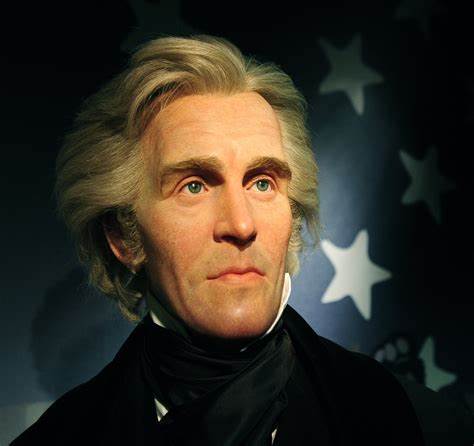

As we reported last week, Texas won its independence from Mexicoduring the administration of President Andrew Jackson. It thenwanted to become part of the United States.

Jackson wanted to make Texas a state in the union. But moreimportant to him was the union itself. Jackson felt that to givestatehood to Texas would deepen the split between the northern andsouthern states. Texas would be a slave state. For this reason,Texas statehood was strongly opposed by the anti-slavery leaders inthe north.

Jackson told Texas minister William Wharton that there was a waythat statehood for Texas would bring the north and south together,instead of splitting them apart.

VOICE TWO:

Jackson said Texas should claimCalifornia. The fishing interests of the north and east, saidJackson, wanted a port on the Pacific coast. Offer it to them, thepresident said, and they will soon forget the spreading of slaverythrough Texas.

Jackson and Wharton held this discussion just three weeks beforethe end of the president’s term. Wharton spent much time at theWhite House.

He also worked with congressmen, urging the lawmakers torecognize Texas. He was able to get Congress to include in a bill astatement permitting the United States to send a minister to Texas.Such a minister was to be sent whenever the president receivedsatisfactory evidence that Texas was an independent power. This billwas approved four days before the end of Jackson’s term.

VOICE ONE:

Wharton went back to the White House. Again and again he gaveJackson arguments for recognizing Texas. On the afternoon of Marchthird, eighteen-thirty-seven, Jackson agreed to recognize the newrepublic led by his old friend, Sam Houston. He sent to Congress hisnomination for minister to Texas. One of the last acts of thatCongress was to approve the nomination. The United States recognizedTexas as an independent republic. But nine years would pass beforeTexas became a state.

The fourth of March, eighteen-thirty-seven, was a bright,beautiful day. The sun warmed the thousands who watched the power ofgovernment pass from one man to another.

Andrew Jackson left the White House with the man who would takehis place, Martin Van Buren. They sat next to each other as thepresidential carriage moved down Pennsylvania Avenue toward theCapitol building. Cheers stopped in the throats of the thousands whostood along the street. In silence, they removed their hats to showhow much they loved this old man who was stepping down.

“For once,” wrote Senator Thomas Hart Benton, “the rising sun waseclipsed by the setting sun.”

VOICE TWO:

The big crowd on the east side of the Capitol grew quiet whenJackson and Van Buren walked out onto the front steps of thebuilding. After Chief Justice Taney swore in President Van Buren,the new president gave his inaugural speech. Then Andrew Jacksonstarted slowly down the steps. A mighty cheer burst from the crowd.

“It was a cry,” wrote Senator Benton, “such as power nevercommanded, nor man in power received. It was love, gratitude andadmiration. I felt a feeling that had never passed through mebefore.”

Why was this, men have asked? Why did the people love Jackson so?

Senator Daniel Webster gave this reason: “General Jackson is anhonest and upright man. He does what he thinks is right. And he doesit with all his might.”

Another Senator put it this way: “He called himself ‘the people’sfriend’. And he gave proofs of his sincerity. General Jacksonunderstood the people of the United States better, perhaps, than anypresident before him.”

VOICE ONE:

Jackson was always willing to let the people judge his actions.He was ready to risk his political life for what he believed in.Jackson’s opposition could not understand why the people did notdestroy him. They said he was lucky. “Jackson’s luck” the oppositioncalled it.

Jackson seemed always to win whatever struggle he began. And themen he fought against were not weak opponents. They were politicalgiants: Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun, Nicholas Biddle. The oldgeneral fought these men separately and, at times, all together.

VOICE TWO:

The day after Van Buren becamepresident, Jackson met with a few of his friends. Frank Blair, theeditor of Jackson’s newspaper, was one of them. Senator Benton wasanother. It was a warm, friendly meeting. They thought back overJackson’s years in the White House and talked about what had beendone.

Jackson said he thought his best piece of work was getting rid ofthe Bank of the United States. He said he had saved the people froma monopoly of a few rich men. Someone asked about Texas. Jacksonsaid he was not worried about Texas. That problem would solveitself, he said.

Did the general have any regrets about anything? “Only two,” saidJackson. “I regret I was unable to shoot Henry Clay or to hang JohnC. Calhoun.”

VOICE ONE:

The next morning, March sixth, Jackson left Washington to returnto his home in Tennessee. President Van Buren protested that Jacksonwas not well enough to travel. The old man had been sick for thelast few months of his presidency. He suffered from tuberculosis,and at times lost great amounts of blood from his lungs. WhenJackson refused to listen to Van Buren’s protests, the presidentsent the army’s top doctor, Surgeon General Thomas Lawson, to travelwith Jackson.

General Jackson was to leave the capital by train. Thousands ofpeople lined the streets to the train station, waiting for a lastlook at their president. Jackson stood in the open air on the rearplatform of the train. His hat was off, and the wind blew throughhis long white hair.

Not a sound came from the people who crowded around the back ofthe train. A bell rang. There was a hiss of steam. And the trainbegan to move. General Jackson bowed. The crowd stood still. Thetrain moved around a curve and could no longer be seen. The crowdbegan to break up. One man who was there said it was as if a brightstar had gone out of the sky.

VOICE TWO:

Jackson lived for eight more years. He died as he had lived…withdignity and honor.

A few hours after his death, a tall man and a small child arrivedat the Jackson home. They had traveled a long way — all the wayfrom Texas. The big man was Sam Houston, the president of Texas. Hehad heard that his friend was dying.

Houston was too late to say goodbye. He stood before Jackson’sbody, tears in his eyes. Then Houston dropped to his knees andburied his face on the chest of his friend and chief. He pulled thesmall boy close to him. “My son,” he said, “try to remember that youhave looked on the face of Andrew Jackson.”

VOICE ONE:

Andrew Jackson stepped down from the presidency in March,eighteen-thirty-seven. His presidential powers were passed to hismost trusted political assistant, Martin Van Buren of New York.

Van Buren was elected president after campaign promises tocontinue the policies of Jackson. He was opposed by severalcandidates, all of the new Whig Party. Van Buren won easily with thehelp of Andrew Jackson.

Years before, Van Buren had done much himself to elect Jackson tothe White House. After the election of eighteen-twenty-four haddivided the opponents of John Quincy Adams, Van Buren began to puttogether a political alliance for the future.

We will continue our story on Van Buren next week.

(MUSIC)

VOICE TWO:

You have been listening to the Special English program, THEMAKING OF A NATION. Your narrators were Gwen Outen and Doug Johnson.Our program was written by Frank Beardsley. THE MAKING OF A NATIONcan be heard Thursdays.