(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

THE MAKING OF A NATION — a program in Special English.

(MUSIC)

As the American national election of eighteen-forty drew closer, the Whig Party felt more and more hopeful that it could put its candidate in the White House. The Whigs believed they could defeat President Martin Van Buren in his attempt to win a second term. The Whig leaders turned away from their early choice of Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky as their candidate. There was too much popular opposition to him.

The more extreme anti-slavery groups were opposed to Clay because he owned slaves. Then, many were hostile to Clay because of his close ties to the business interests. They considered him a pro-bank man. Besides, there was a growing feeling among the Whig leaders that they should choose a military hero as their presidential candidate…a general like Andrew Jackson.

VOICE TWO:

Thurlow Weed, one of the important Whig leaders in the state of New York, remembered how the people had loved Jackson, the hero of the War of 1812. Weed thought General William Henry Harrison, one of the candidates in eighteen-thirty-six, might be the man the Whigs needed. Harrison had led an attack on Indians in the Indiana territory in eighteen-eleven.

Westerners believed the battle — at a place called Tippecanoe — was a great victory for Harrison. Weed also thought of General Winfield Scott, who had kept the border with Canada quiet. Scott was a southerner, from Virginia. He had not been involved in politics and had no political enemies. Weed finally decided that Scott might be a better candidate than Harrison or Clay.

VOICE ONE:

But other party leaders remembered that Harrison had received many votes in eighteen-thirty-six, although not enough to win. When the Whig convention opened, all three men — Clay, Scott, Harrison — were possible candidates. The convention delegates finally chose General Harrison. For vice president, they decided on another southerner, John Tyler. Tyler was a strong believer in states’ rights. He had worked hard to win the nomination for Senator Clay. One report said he felt so strongly about it that he cried when Clay was not chosen. Southern Whigs agreed to support Harrison only because Tyler was the vice presidential candidate.

VOICE TWO:

Clay was not at the convention. He stayed in Washington and waited for news from the convention. On the final day, as he waited for word, he drank glass after glass of wine. When the news came that the Whigs had chosen Harrison, Clay said in anger: “I am the most unfortunate man in the history of parties. Always chosen as a candidate when sure to be defeated. And now, tricked out of the nomination when I, or anyone, would surely be elected.”

The Democrats were happy that Clay was not the Whig presidential candidate. They were glad the whigs chose the sixty-seven-year-old Harrison. Democrats spoke of Harrison as an “old lady.” They called him “Granny Harrison.” One democratic newspaper said the old man did not really want to be president. It said Harrison would be happier with a two-thousand-dollar-a-year pension, a barrel of hard cider to drink, and a log cabin to live in.

VOICE ONE:

Working men drank hard apple cider. And a great many farmers still lived in houses, or cabins, made of rough logs. The Whigs put the democratic statement to their own use. They saw a way to represent their party of bankers and businessmen as the party of the working man and the small farmer. “The statement is right!” they cried. “The Whig Party is the party of hard cider and log cabins.”

They made Harrison — a Virginia aristocrat — a simple man of the people. His big home in Ohio became a log cabin. He exchanged his silk hat for the kind worn by farmers. Whig leaders would not let their candidate make many speeches. They would not let him write anything. All his letters were written by his political advisers. When Harrison did speak in public, it usually was about nothing important. No one really knew what the old man thought about any of the important issues.

VOICE TWO:

The Democrats opened their nominating convention in Baltimore in may, eighteen-forty. Van Buren was chosen to be the party’s candidate again. The president received the votes of all the party representatives at the convention. But the representatives were not able to agree on a vice presidential candidate. They finally decided to let the states nominate candidates for the job.

The election campaign was one of the wildest in the nation’s history. Both parties did everything possible to show that they were the friend of the common man. The Whigs put up log cabins everywhere and offered free hard cider to everyone. They organized huge outdoor meetings for thousands, with food and drink for all. They held parades and marched with flags, bands, and pictures of William Henry Harrison. Many campaign songs were written. These songs told of Harrison’s bravery against the Indians. They told how Harrison loved the hard and simple life of the common man.

VOICE ONE:

At the same time, the Whig campaign songs said Van Buren lived like a king in the White House. A Whig congressman from Pennsylvania made a wild speech against the president. Copies of it were spread throughout the country. The congressman charged that the White House had become a palace. He said Van Buren slept in the same kind of bed as the one used by the French King, Louis the Fifteenth. He said the president ate French food from gold and silver dishes. The carpets in the White House, he said, were so thick that a man could bury his feet in them. The congressman charged that President Van Buren wore silk clothing, and even put French perfume on his body to make him smell sweet as a flower.

VOICE TWO:

Van Buren and other Democrats called the charges foolish. But no one seemed to hear. The Democrats made charges just as foolish. They claimed that Harrison could not read or write. They said he would not pay people the money he owed them. And they charged that Harrison even sold white men into slavery. Henry Clay said the campaign was a struggle between log cabins and palaces…between hard cider and champagne.

The state of Maine held elections in September of eighteen-forty. Voters in Maine elected Whig Edward Kent as governor. They gave the state’s electoral votes to Harrison, the hero of Tippecanoe. The election results produced a new song for the whigs. “And have you heard the news from Maine, and what old Maine can do. She went hell-bent for Governor Kent, and Tippecanoe and Tyler, too. And Tippecanoe and Tyler, too. “

VOICE ONE:

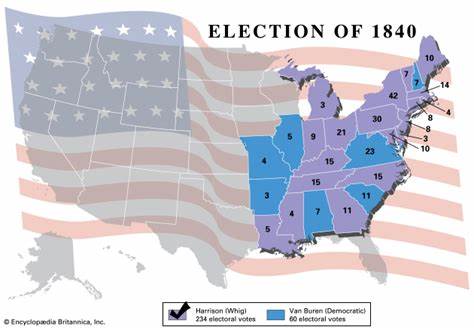

One by one, the other states voted. It was clear early in the election that General Harrison would win. The election was close in total votes. But Harrison received two-hundred thirty-four electoral votes, and Van Buren only sixty. And so, Harrison became the ninth president of the United States.

Whig leaders had made most of Harrison’s campaign decisions. Some of them — especially Henry Clay and Daniel Webster — believed they could continue to control him, even after Harrison moved into the White House. But Harrison saw what was happening. He made a trip to Kentucky, Clay’s home state, late in eighteen-forty. Harrison made it clear that he did not want to meet with Clay. He was afraid such a meeting would seem to show that Clay was the real power in the new administration.

(MUSIC)

VOICE TWO:

You have been listening to the Special English program, THE MAKING OF A NATION. Your narrators were Jack Moyles and Jack Weitzel. Our program was written by Frank Beardsley. THE MAKING OF A NATION can be heard Thursdays.