(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

THE MAKING OF A NATION — a program in Special English by the Voice of America.

(MUSIC)

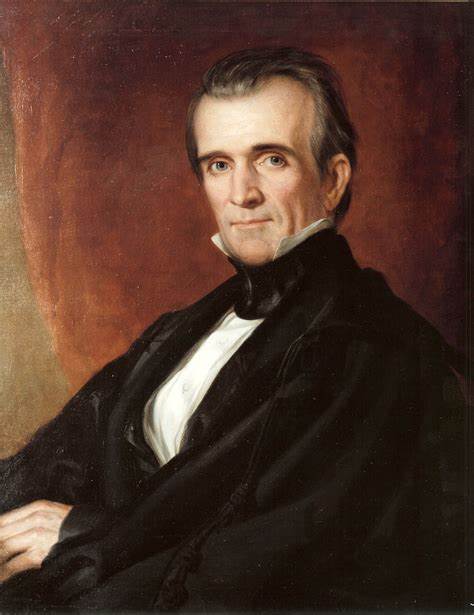

In the middle eighteen-forties, the United States offered to buy California from Mexico. The government of Mexico refused to negotiate. American President James Polk felt that the use of force was the only way to make Mexico negotiate. So, in the spring of eighteen-forty-six, he ordered American soldiers to the Rio Grande River. The Rio Grande formed part of the border between the United States and Mexico.

VOICE TWO:

General Zachary Taylor commanded the American force. He sent one of his officers across the river to meet with Mexican officials. The Mexicans protested the movement of the American troops to the Rio Grande. They said the area was Mexican territory. The movement of American troops there, they said, was an act of war.

For almost a month, the Americans and the Mexicans kept their positions. Then, on April twenty-fifth, General Taylor received word that a large Mexican force had crossed the border a few kilometers up the river. A small force of American soldiers went to investigate. They were attacked. All were killed, wounded, or captured. General Taylor quickly sent a message to President Polk in Washington. It said war had begun.

VOICE ONE:

The message arrived at the White House on May ninth. A few days later, President Polk asked Congress to recognize that war had started. He asked Congress to give him everything he needed to win the war and bring peace to the area. A few members of Congress did not want to declare war against Mexico. They believed the United States was responsible for the situation along the Rio Grande. They were out-voted. President Polk signed the war bill. Later, Polk wrote:

“We had not gone to war for conquest. But it was clear that in making peace we would, if possible, get California and other parts of Mexico.”

VOICE TWO:

Many Americans opposed what they called “Mr. Polk’s war.” Whig Party members and Abolitionists in the north believed that slave-owners and southerners in Polk’s administration had planned the war. They believed the south wanted to win Mexican territory for the purpose of spreading and strengthening slavery.

President Polk was troubled by this opposition. But he did not think the war would last long. He thought the United States could quickly force Mexico to sell him the territory he wanted. Polk secretly sent a representative to former Mexican dictator Santa Ana. Santa Ana was living in exile in Cuba. Polk’s representative said the United States wanted to buy California and some other Mexican territory. Santa Ana said he would agree to the sale, if the United States would help him return to power.

VOICE ONE:

President Polk ordered the United States navy to let Santa Ana return to Mexico. American ships that blocked the port of Vera Cruz permitted the Mexican dictator to land there. Once Santa Ana returned, he failed to honor his promises to Polk. He refused to end the war and sell California. Instead, Santa Ana organized an army to fight the United States.

American General Zachary Taylor moved against the Mexicans. He crossed the Rio Grande River. He marched toward Monterrey, the major trading and transportation center of northeast Mexico. The battle for Monterrey lasted three days. The Mexicans surrendered.

VOICE TWO:

Then General Taylor got orders to send most of his forces back to the coast. They were to join other American forces for the invasion of Vera Cruz. While this was happening, Santa Ana was moving his army north. In four months, he had built an army of twenty-thousand men. When General Taylor learned that Santa Ana was preparing to attack, he left Vera Cruz. He moved his forces into a position to fight Santa Ana.

VOICE ONE:

Santa Ana sent a representative to meet with General Taylor. The representative said the American force had one hour to surrender. Taylor’s answer was short: “Tell Santa Ana to go to hell.”

The battle between the United States and Mexican forces lasted two days. Losses were heavy on both sides. On the second night, Santa Ana’s army withdrew from the battlefield. Taylor had won another victory.

VOICE TWO:

Other American forces were victorious, too. General Winfield Scott had captured the port of Vera Cruz and was ready to attack Mexico City. Commodore Robert Stockton had invaded California and had raised the American flag over the territory.

Stephen Kearny had seized Santa Fe, the capital of New Mexico, without firing a shot. Still, the war was not over. President Polk’s “short” war already had lasted for more than a year. Polk decided to send a special diplomatic representative to Mexico. He gave the diplomat the power to negotiate a peace treaty whenever Mexico wanted to stop fighting.

VOICE ONE:

A ceasefire was declared. But attempts to negotiate a peace treaty failed. Santa Ana tried to use the ceasefire to prepare for more fighting. So General Scott ended the ceasefire. His men began their attack on Mexico City. The fighting lasted one week. The government of Mexico surrendered. Santa Ana stepped down as president. Manuel de la Pena y Pena — president of the supreme court — became acting president.

VOICE TWO:

On February second, eighteen-forty-eight, the United States and Mexico signed a peace treaty. Mexico agreed to give up California and New Mexico. It would recognize the Rio Grande River as the southern border of Texas. The United States would pay Mexico fifteen-million dollars. It also would pay more than three-million dollars in damage claims that Mexico owed American citizens.

The terms of the treaty were those set by President Polk. Yet he was not satisfied with just California and New Mexico. He wanted even more territory. But he realized he probably would have to fight for it. And he did not think Congress would agree to extend the war. So polk sent the peace treaty to the Senate. It was approved. The mexican Congress also approved it. The war was officially over.

VOICE ONE:

The United States now faced the problem of what to do with the new lands. President Polk wanted to form territorial governments in California and New Mexico. He asked Congress for immediate permission to do that. But the question of slavery delayed quick congressional action. Should the new territories be opened or closed to slavery. Southerners argued that they had the right to take slaves into the new territories. Northerners disagreed. They opposed any further spread of slavery. The real question was this: did Congress have the power to control or bar slavery in the territories.

VOICE TWO:

Until Texas became a state, almost all national leaders seemed to accept the idea that Congress did have this power. For fifty years, Congress had passed resolutions and laws controlling slavery in United States territories. Northerners believed Congress received the power from the constitution. Southern slave owners disagreed. They believed the power to control slavery remained with the states.

VOICE ONE:

There were some who thought the earlier Missouri Compromise could be used to settle the issue of slavery in California, Oregon, and New Mexico. They proposed that the line of the Missouri Compromise be pushed west, all the way to the Pacific Coast. Territory north of the line would be free of slavery. South of the line, slavery would be permitted.

Everyone agreed that governments had to be organized in the territories. But there seemed to be no way to settle the issue of slavery. Then a Senator from Delaware agreed to be chairman of a special committee on the question of slavery in the new territories. The Senate committee included four Whigs and four Democrats. North and south were equally represented. Within six days, the committee had agreed on a compromise bill. That will be our story next week.

(MUSIC)

VOICE TWO:

You have been listening to the Special English program, THE MAKING OF A NATION. Your narrators were Maurice Joyce and Larry West. Our program was written by Frank Beardsley.