(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

This is Shirley Griffith.

VOICE TWO:

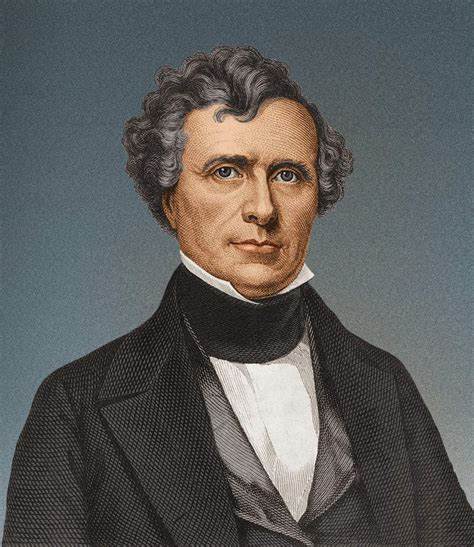

And this is Rich Kleinfeldt with the VOA Special English history program, THE MAKING OF A NATION. Today,we continue the story of America’s fourteenth president, Franklin Pierce.

(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

Franklin Pierce was elected in eighteen-fifty-two. He was a compromise candidate of the Democratic Party. He was well-liked. But he was not considered a strong leader.

The eighteen-fifties were an increasingly tense time in the United States. Most of the population lived east of the Mississippi River. However, more and more people were moving west. As western areas became populated, they became official territories and then new states.

What kind of laws would the new territories and states have. Would the laws be decided by the Congress in Washington. Or would they be voted on by the people living there.

The biggest legal question affecting western lands was slavery.

VOICE TWO:

Owning another human being was legal in many parts of the United States at that time. Slaves were considered property, like furniture and farm animals.

People who owned negro slaves wanted to take all their property — including the slaves — with them when they moved west. People who opposed slavery did not want it to spread. Some of them considered slavery a moral issue. They believed it violated the laws of God. An increasing number of white Americans, however, saw slavery as an economic issue. They wanted new states to be free from slavery, so they would not have to compete with slave labor.

VOICE ONE:

The United States had been established as a democracy. Yet slavery existed. America’s early leaders knew that trying to end slavery probably would split the nation in two. So they looked for compromises. They decided it was better to save the Union…even if it was not perfect…than to watch the Union end.

Like other presidents, Franklin Pierce hoped to avoid the issue. He also believed that earlier legislation had settled the debate. In eighteen-twenty, Congress had passed the Missouri Compromise. It extended a line across the map of the United States. South of the line, slavery was legal. North of the line, slavery was not legal, except in Missouri.

Thirty years later, another political compromise made the situation less clear.

VOICE TWO:

The compromise of eighteen-fifty made slavery a local issue, instead of a national issue, in several western territories. It said the people in those territories had the right to decide for themselves if slavery would be legal or illegal.

Within a few years, that law caused a new debate in Congress. Lawmakers argued: was the peoples’ right to decide the issue of slavery restricted only to the territories named in the compromise of eighteen-fifty? Or was the right extended to the people of all future territories?

VOICE ONE:

The answer came in eighteen-fifty-four. In that year, Congress debated a proposal to create two territories from one large area in the west. The northern part would be known as the Nebraska territory. The southern part would be known as the Kansas territory. Settlers in both new territories would have the right to decide the question of slavery.

President Pierce did not like the Kansas-Nebraska bill. He feared it would re-open the bitter, national debate about slavery. He did not want to have to deal with the results. Tensions were increasing. Violence was increasingly possible.

The Kansas-Nebraska bill had a lot of support in the Senate. It passed easily. The bill had less support in the House of Representatives. The vote there was close, but the measure passed. President Pierce finally agreed to sign it. In exchange, congressional leaders promised to approve several presidential appointments.

Supporters of the Kansas-Nebraska bill celebrated their victory. They fired cannons as the city of Washington was waking to a new day. Two senators who opposed the bill heard the noise as they walked down the steps of the capitol building. One of them said: “They celebrate a victory now. But the echoes they awake will never rest until slavery itself is dead.”

VOICE TWO:

The new bill gave the people of Kansas and Nebraska the right to decide if slavery would be legal or illegal. The vote would depend on who settled in the territories. It was not likely that people who owned slaves would settle in Nebraska. However, there was a good chance that they would settle in Kansas.

Groups in the south organized quickly to help pro-slavery settlers move to Kansas. At the same time, groups in the north helped free-state settlers move there, too.

VOICE ONE:

Some of the northern groups were companies called emigrant aid societies. Shares of these companies were sold to the public. The money was used to help build towns and farms in Kansas. Owners of the companies hoped to make a lot of money from the development.

The southern effort to settle Kansas was led mostly by slave-owning farmers in Missouri. They believed that peace in Missouri depended on what happened in Kansas. They did not want to live next to a territory where slavery was not legal.

VOICE TWO:

In Washington, President Pierce announced the appointment of Andrew Reeder to be governor of the Kansas territory. Pro-slavery settlers urged Reeder to hold immediate elections for a territorial legislature. They believed they were in the majority. They wanted a vote before too many free-state settlers moved in. The legislature would have the power to keep the territory open to slavery and, in time, help it become a slave state.

VOICE ONE:

Governor Reeder rejected the demands. He decided to hold an election, but only for a territorial representative to the national Congress. On election day, hundreds of men from Missouri crossed the border into Kansas. They voted illegally, and the pro-slavery candidate won.

The same thing happened when Kansas finally held an election for a legislature. Governor Reeder took steps to make the voting fair. His efforts were not completely successful. Once again, men from Missouri crossed the border into Kansas. Many of them carried guns. They forced election officials to count their illegal votes. As a result, almost every pro-slavery candidate was elected to the new legislature.

VOICE TWO:

The governor ordered an investigation. The investigation showed evidence of wrong-doing in six areas, and new elections were held in those areas. This time, when only legal votes were counted, many of the pro-slavery candidates were defeated. Yet there were still enough pro-slavery candidates to have a majority.

VOICE ONE:

Andrew Reeder was governor of a bitterly divided territory. He wanted to warn President pierce about what was happening.

Reeder went to Washington. He met with Pierce almost every day for two weeks. He described how pro-slavery groups in Missouri were interfering in Kansas. He said if the state of Missouri refused to deal with the trouble-makers, then the national government must deal with them. He asked the president to do something.

VOICE TWO:

Pierce agreed that Kansas was a serious problem. He seemed ready to act. So reeder returned home and opened the first meeting of the territorial legislature. The pro-slavery majority quickly voted to move to a town close to the Missouri border. It also approved several pro-slavery measures.

Governor Reeder vetoed these bills. But there were enough votes to reject his veto and pass the new laws.

VOICE ONE:

The Kansas legislature also sent a message to President Pierce. It wanted him to remove Andrew Reeder as governor. Political pressure was strong, and the president agreed. He named a new governor, Wilson Shannon. Shannon supported the pro-slavery laws of the legislature. He also said Kansas should become a slave state, like Missouri.

Free-state leaders were extremely angry. They felt they could not get fair treatment from either the president or the new governor. So they took an unusual step. They met and formed their own government in opposition to the elected government of the territory. It would not be long before the situation in Kansas became violent. That will be our story next week.

(MUSIC)

VOICE TWO:

Today’s program of THE MAKING OF A NATION was written by Christine Johnson. This is Rich Kleinfeldt.

VOICE ONE:

And this is Shirley Griffith. Join us again next time for another VOA Special English report about the history of the United States.