(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

THE MAKING OF A NATION — a program in Special English by the Voice of America.

(MUSIC)

South Carolina withdrew from the United States on December twentieth, eighteen-sixty. It withdrew because a Republican, Abraham Lincoln, had been elected president. The Republican Party wanted to stop slavery from spreading into the western territories. Southern states believed they had a constitutional right to take property, including slaves, anywhere. They also feared that any interference with slavery would end their way of life.

I’m Larry West. Today, Frank Oliver and I tell what happened after South Carolina seceded from the Union.

VOICE TWO:

South Carolina faced several problems after it seceded. The most serious problem was what to do with property owned by the federal government. There were several United States forts in and around the Port of Charleston. Fort Moultrie had fewer than seventy soldiers. Castle Pinckney had only one. And Fort Sumter, which was still being built, had none.

The commander of the forts asked for more men. Without them, he said, he could not defend the forts. The army refused. It told the commander to defend the forts as best he could. He was told to do nothing that might cause South Carolina to attack. If South Carolina attacked, or planned to attack, then he could move his men into the fort that would be easiest to defend. That would probably be the new one, Fort Sumter.

VOICE ONE:

The governor of South Carolina planned to stop any movement of federal troops. He ordered state soldiers to stop every boat in Charleston Harbor. They were to permit no United States troops to reach Fort Sumter. If any boat carrying troops refused to stop, the state soldiers were to sink it and seize the fort.

Six days after South Carolina seceded from the Union, the commander of Charleston’s forts decided to move his men to Fort Sumter. They would move as soon as it was dark.

The federal troops crossed the port in small boats. The state soldiers did not see them. The governor was furious when he learned what had happened. He demanded that the federal troops leave Fort Sumter. The commander said they would stay.

The governor then ordered state soldiers to seize the other two forts in Charleston Harbor. And he ordered the state flag raised over all other federal property in the city.

VOICE TWO:

President James Buchanan, who would leave office in just a few months, was forced to deal with the situation. His cabinet was deeply divided on the issue. The southerners wanted him to recognize South Carolina and order all federal troops out of Charleston Harbor. The northerners said he must not give up any federal property or rights.

The President agreed to meet with three representatives from South Carolina. They had come to Washington to negotiate the future of federal property in their state. The Attorney General said the meeting was a mistake.

“These gentlemen,” he said, “claim to be ambassadors of South Carolina. This is foolish. They cannot be ambassadors. They are law-breakers, traitors, and should be arrested. You cannot negotiate with them.”

VOICE ONE:

The Attorney General and the Secretary of State threatened to resign if President Buchanan gave in to South Carolina’s demands. The President finally agreed not to give in.

He said he would keep federal troops in Charleston Harbor. And he said Fort Sumter would be defended against all hostile action. On the last day of eighteen-sixty, he ordered two-hundred troops and extra supplies sent to Fort Sumter.

The war department wanted to keep the operation secret. So the troops and supplies were put on a fast civilian ship, instead of a slower warship. It was thought that a civilian ship could get into Charleston Harbor before state forces could act.

But a southern Senator learned of the operation. He warned the governor of South Carolina. When the ship arrived in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina soldiers were waiting.

VOICE TWO:

The soldiers lit a cannon and fired a warning shot. The ship refused to stop. Other cannons then opened fire.

The commander of federal troops at Fort Sumter had a difficult decision to make. He had received permission to defend the fort, if attacked. But his orders said nothing about defending ships. He knew that if he opened fire, the United States and South Carolina would be at war.

The decision was made for him. South Carolina’s cannons finally hit the ship. The ship slowed, then turned back to sea. It returned north with all the troops and supplies.

VOICE ONE:

The commander of Fort Sumter sent a message to the governor of South Carolina.

“Your forces,” he wrote, “fired this morning on a civilian ship flying the flag of my government. Since I have not been informed that South Carolina declared war on the United States, I can only believe that this hostile act was done without your knowledge or permission. For this reason — and only this — I did not fire on your guns.”

If, the commander said, the governor had approved the shelling, it would be an act of war. And he would be forced to close the Port of Charleston. No ship would be permitted to enter or leave.

The governor’s answer came back within hours. He said South Carolina was now independent. He said the attempt by the United States to strengthen its force at Fort Sumter was clearly an act of aggression. And he demanded that the commander surrender.

VOICE TWO:

During the crisis over Fort Sumter, Congress tried to find a compromise that might prevent war. Lawmakers proposed a new line across the country. South of the line, slavery would be permitted. North of the line, slavery would be illegal.

Many Republicans supported the proposal, even though the Republican Party opposed the spread of slavery into the western territories.

One Republican, however, rejected the idea completely. He was Abraham Lincoln, who would take office as President in March. Lincoln said there could be no compromise on extending slavery. “If there is,” he said, “then all our hard work is lost. If trouble comes, it is better to let it come now than at some later time.”

VOICE ONE:

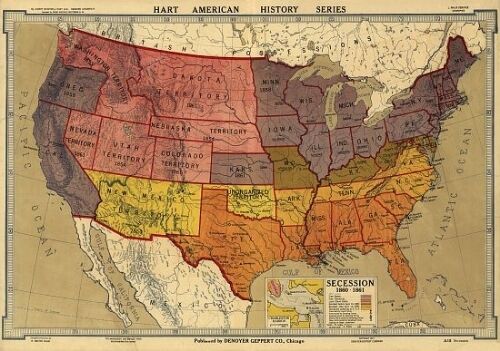

The trouble would come soon. One by one, the states of the south seceded.

By February first, eighteen sixty-one, six states had followed South Carolina out of the Union. A few days later, representatives from the states met in Montgomery, Alabama. Their job was to create a new nation. It would be an independent republic called the Confederate States of America.

The convention approved a constitution for the new nation. The document was like the Constitution of the United States, but with major changes. The southern constitution gave greater importance to the rights of states. And it said there could be no laws against slavery.

The convention named former United States Senator Jefferson Davis to be president of the Confederate States of America.

Davis did not want civil war. But he was not afraid of it. He said: “Our separation from the old Union is complete. The time for compromise has passed. Should others try to change our decision with force, they will smell southern gunpowder and feel the steel of southern swords.”

VOICE TWO:

Jefferson Davis left his farm in Mississippi to become President of the Confederate States of America on February eleventh. On that same day, Abraham Lincoln left his home in Illinois to become President of the United States.

As Lincoln got on the train that would take him to Washington, he said:

“I now leave, not knowing when — or whether ever — I may return. The task before me is greater than that which rested upon our first president. Without the help of God, I cannot succeed. With that assistance, I cannot fail. Let us hope that all yet will be well.”

(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

You have been listening to the Special English program, THE MAKING OF A NATION. Your narrators were Larry West and Frank Oliver. Our program was written by Frank Beardsley.