(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

THE MAKING OF A NATION — a program in Special English.

(MUSIC)

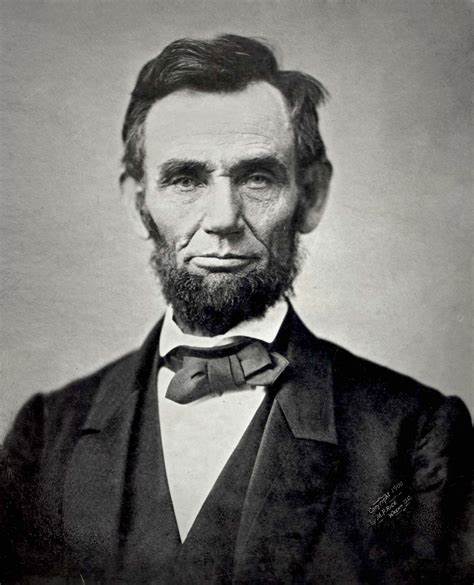

On a cold and cloudy day in March, eighteen-sixty-one, Abraham Lincoln became the sixteenth president of the United States. In his inaugural speech, the new president announced the policy he would follow toward the southern states that had left the Union.

Lincoln said no state had a legal right to secede. He said the Union could not be broken. He said he would enforce federal laws in every state. And he promised not to surrender any federal property in the states that seceded. Lincoln said if force was necessary to protect the Union, then force would be used.

His policy was soon tested.

VOICE TWO:

On his second day as President, Lincoln received some bad news from Fort Sumter at Charleston, South Carolina. Major Robert Anderson, the commander of the small United States force at Sumter, wrote that his food supplies were low. At most, said Anderson, there was enough food for forty days. Unless he and his men received more supplies, they would have to leave the fort.

Lincoln wanted to keep Fort Sumter. It was one of the few United States forts in the south still held by federal forces. And he had promised not to give up any federal property in the states that seceded.

VOICE ONE:

But getting food to Fort Sumter would be a very difficult job. The fort was built on an island in Charleston Harbor. It was surrounded by southern artillery. Southern gunboats guarded the port.

To get supplies to Anderson and his men, a ship would have to fight its way to Sumter. Such a battle was sure to begin a bitter civil war. There also was the danger that fighting would cause slave states still in the Union to secede and join the southern Confederacy.

VOICE TWO:

The Army Chief, General [Winfield] Scott, warned Lincoln that it was too late to get supplies to Fort Sumter. He said southern defenses around the fort were so strong that a major military effort would be necessary. He said it would take months to prepare the warships and soldiers for such an effort. Major Anderson and his men at Sumter, he said, could not wait that long.

There was another plan, however, that might work. It was proposed to Lincoln by Captain Gustavus Fox of the Navy Department.

Captain Fox said soldiers and supplies could be sent down to Charleston in ships. Outside the entrance to the harbor, on a dark night, they could be put into small boats and pulled by tugs to the fort. Fox said a few warships could be sent to prevent southern gunboats from interfering.

VOICE ONE:

Lincoln liked this plan. He asked his cabinet for advice. If it were possible to send supplies to Sumter, he asked, would it be wise to do so?

Postmaster General [Montgomery] Blair was the only member of the cabinet to answer ‘yes’. Treasury Secretary [Salmon] Chase was for the plan only if Lincoln was sure it would not mean war. Secretary of State [William] Seward and the others opposed it. They said it would be better to withdraw Major Anderson and his men. They felt that now was not the time to start a civil war.

This opposition in the cabinet caused Lincoln to postpone action on the Fox plan. But he sent two men separately to Charleston to get him information on the situation there. One was Captain Fox. The other was a close friend, Ward Lamon.

VOICE TWO:

In Charleston, Fox met with Governor [Francis] Pickens. He explained that he wished to talk with Major Anderson, not to give him orders, but to find out what the situation really was. Governor Pickens agreed. A Confederate boat carried Fox to Sumter. Anderson told Fox that the last of the food would be gone on April fifteenth.

Ward Lamon went to Charleston after Fox returned to Washington. He, too, met with Governor Pickens and Major Anderson. The South Carolina Governor asked Lamon to give Lincoln this message:

“Nothing can prevent war except a decision by the President of the United States to accept the secession of the south. If an attempt is made to put more men in Fort Sumter, a war cry will be sounded from every hilltop and valley in the south.”

Lamon reported to Lincoln that the arrival of even a boat load of food at sumter would lead to fighting.

VOICE ONE:

At the end of March, Lincoln held another cabinet meeting and again asked what should be done about Fort Sumter. Should an attempt be made to get supplies to Major Anderson. This time, three members of the cabinet voted ‘yes’ and three voted ‘no’.

When the meeting ended, Lincoln wrote an order for the Secretary of War. He told him to prepare to move men and supplies by sea to Fort Sumter. He said they should be ready to sail as early as April sixth — only one week away.

VOICE TWO:

On April fourth, Lincoln called Captain Fox to the White House. He told him that the government was ready to take supplies to Fort Sumter. He said Fox would lead the attempt.

Later in the meeting, Toombs urged Davis not to attack the fort.

“Mr. President,” he said, “at this time it is suicide — murder — and will lose us every friend in the north. You will strike a hornets’ nest which extends from mountains to oceans. Millions now quiet will swarm out and sting us to death. It is not necessary. It puts us in the wrong. It will kill us!”

VOICE TWO:

On April tenth, Jefferson Davis sent his decision to the Confederate commander at Charleston, General Pierre Beauregard. He told Beauregard to demand the surrender of Fort Sumter. If Major Anderson refused, then the general was to destroy the fort.

The surrender demand was carried to Sumter the next day by a group of Confederate officers. They said Anderson and his men must leave the fort. But they could take with them their weapons and property. And they were offered transportation to any United States port they named.

VOICE ONE:

Anderson rejected the demand. As he walked with the Confederate officers back to their boat, he asked if General Beauregard would open fire on Sumter immediately. No, they said, he would be told later when the shooting would start. Anderson then told the southerners, “If you do not shell us to pieces, hunger will force us out in a few days.”

General Beauregard informed the Confederate government in Montgomery that Anderson refused to surrender. He also reported the major’s statement that Sumter had only enough food for a few more days.

VOICE TWO:

New orders were sent to Beauregard. Jefferson Davis said there was no need to attack the fort if hunger would soon force the United States soldiers to leave. But he said Anderson must say exactly when he and his men would leave. And he said Anderson must promise not to fire on Confederate forces. If anderson agreed to this, then Confederate guns would remain silent.

This offer was carried to Fort Sumter a few minutes before midnight, April eleventh.

Anderson discussed the offer with his officers and then wrote his answer. He would leave the fort on April fifteenth if the Confederates made no hostile act against Fort Sumter or against the United States flag. He would not leave, however, if before then he received new orders or supplies.

VOICE ONE:

This did not satisfy the three confederate officers who brought Beauregard’s message. They handed Anderson a short note. It said: “We have the honor to inform you that General Beauregard will open fire on Fort Sumter in one hour — at twenty minutes after four on the morning of April twelfth, eighteen-sixty-one.”

The major shook hands with Beauregard’s representatives, and they left the fort. Anderson and his officers woke their men and told them to prepare for battle.

At Fort Johnson, across the harbor, Confederate gunners also were getting ready. These men would fire the first shot at Sumter. That explosion would signal the other guns surrounding the fort to open fire.

VOICE TWO:

You have been listening to the Special English program, THE MAKING OF A NATION. Your narrators were Jack Moyles and Jack Weitzel. Our program was written by Frank Beardsley. THE MAKING OF A NATION can be heard Thursdays.