(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

THE MAKING OF A NATION — a program in Special English.

(MUSIC)

Just before sunrise on the morning of April twelfth, eighteen-sixty-one, the first shot was fired in the American Civil War. A heavy mortar roared, sending a shell high over the harbor at Charleston, South Carolina. The shell dropped and exploded above Fort Sumter, a United States fort on an island in the harbor.

The explosion was a signal for all southern guns surrounding the fort to open fire. Shell after shell smashed into the island fort.

The booming of the cannons woke the people of Charleston. They rushed to the harbor and cheered as the bursting shells lighted the dark sky.

VOICE TWO:

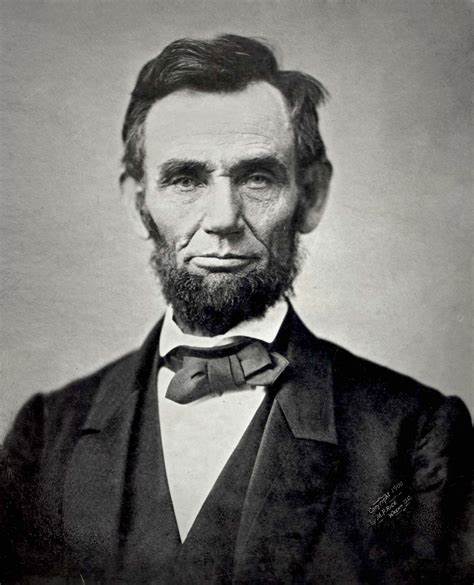

Confederate leaders ordered the attack after President Abraham Lincoln refused to withdraw the small force of American soldiers at Sumter. Food supplies at the fort were very low. And southerners expected hunger would force the soldiers to leave. But Lincoln announced he was sending a ship to Fort Sumter with food.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis ordered his commander in Charleston, General [Pierre] Beauregard, to destroy the fort before the food could arrive.

VOICE ONE:

The attack started from Fort Johnson across the harbor from Sumter. A Virginia Congressman, Roger Pryor, was visiting Fort Johnson when the order to fire was given. The fort’s commander asked Pryor if he would like the honor of firing the mortar that would begin the attack. “No,” answered Pryor, and his voice shook. “I cannot fire the first gun of the war.”

But others could. And the attack began.

VOICE TWO:

At Fort Sumter, Major Robert Anderson and his men waited three hours before firing back at the Confederate guns.

Anderson could not use his most powerful cannons. They were in the open at the top of the fort, where there was no protection for the gunners. Too many of his small force would be lost if he tried to fire these guns.

So Anderson had his men fire the smaller cannon from better-protected positions. These, however, did not do much damage to the Confederate guns.

VOICE ONE:

The shelling continued all day. A big cloud of smoke rose high in the air over Fort Sumter.

The smoke was seen by United States navy ships a few miles outside Charleston Harbor. They had come with the ship bringing food for the men at Sumter. There were soldiers on these ships. But they could not reach the fort to help Major Anderson. Confederate boats blocked the entrance to the harbor. And confederate guns could destroy any ship that tried to enter.

The commander of the naval force, Captain [Gustavus] Fox, had hoped to move the soldiers to Sumter in small boats. But the sea was so rough that the small boats could not be used. Fox could only watch and hope for calmer seas.

VOICE TWO:

Confederate shells continued to smash into Sumter throughout the night and into the morning of the second day. The fires at Fort Sumter burned higher. And smoke filled the rooms where soldiers still tried to fire their cannons.

About noon, three men arrived at the fort in a small boat. One of them was Louis Wigfall, a former United States senator from Texas, now a Confederate officer. He asked to see Major Anderson.

“I come from General Beauregard,” he said. “It is time to put a stop to this, sir. The flames are raging all around you. And you have defended your flag bravely. Will you leave, sir?” Wigfall asked.

VOICE ONE:

Major Anderson was ready to stop fighting. His men had done all that could be expected of them. They had fought well against a much stronger enemy. Anderson said he would surrender, if he and his men could leave with honor.

Wigfall agreed. He told Anderson to lower his flag and the firing would stop.

Down came the United States flag. And up went the white flag of surrender. The battle of Fort Sumter was over.

More than four-thousand shells had been fired during the thirty-three hours of fighting. But no one on either side was killed. One United States soldier, however, was killed the next day when a cannon exploded as Anderson’s men prepared to leave the fort.

VOICE TWO:

The news of Anderson’s surrender reached Washington late Saturday, April thirteenth. President Lincoln and his cabinet met the next day and wrote a declaration that the president would announce on Monday.

In it, Lincoln said powerful forces had seized control in seven states of the south. He said these forces were too strong to be stopped by courts or policemen. Lincoln said troops were needed. He requested that the states send him seventy-five-thousand soldiers. He said these men would be used to get control of forts and other federal property seized from the Union.

VOICE ONE:

Lincoln knew he had the support of his own party. He also wanted northern Democrats to give him full support. So, Sunday evening, a Republican congressman visited the top Democrat of the north, Senator Stephen Douglas.

The congressman urged Douglas to go to the White House and tell Lincoln that he would do all he could to help put down the rebellion in the south. At first, Douglas refused. He said Lincoln had removed Democrats — friends of his — from government jobs and had given the jobs to Republicans. Douglas said he didn’t like this. Anyway, he said, Lincoln probably did not want his advice.

The congressman, George Ashmun, urged Douglas to forget party politics. He said Lincoln and the country needed the Senator’s help. Douglas finally agreed to talk with Lincoln. He and Ashmun went immediately to the White House.

VOICE TWO:

Lincoln welcomed his old political opponent. He explained his plans and read to Douglas the declaration he would announce the next day.

Douglas said he agreed with every word of it except, he said, seventy-five-thousand soldiers would not be enough. Remembering his problems with southern extremists, he urged Lincoln to ask for two-hundred-thousand men. He told the president, “You do not know the dishonest purposes of those men as well as I do.”

Lincoln and Douglas talked for two hours. Then the Senator gave a statement for the newspapers. He said he still opposed the administration on political questions. But, he said, he completely supported Lincoln’s efforts to protect the Union.

Douglas was to live for only a few more months. He spent this time working for the Union. He traveled through the states of the northwest, making many speeches. Douglas urged Democrats everywhere to support the Republican government. He told them, “There can be no neutrals in this war — only patriots or traitors.”

VOICE ONE:

Throughout the north, thousands of men rushed to answer Lincoln’s call for troops. Within two days, a military group from Boston left for Washington. Other groups formed quickly in northern cities and began training for war.

Lincoln received a different answer, however, from the border states between north and south.

Virginia’s governor said he would not send troops to help the north get control of the south. North Carolina’s governor said the request violated the Constitution. He would have no part of it. Tennessee said it would not send one man to help force southern states back into the Union. But it said it would send fifty-thousand troops to defend southern rights.

Lincoln got the same answer from the governors of Kentucky, Arkansas, and Missouri. For several days, it seemed that all these states would secede and join the southern confederacy.

VOICE TWO:

Lincoln worried most about Virginia, the powerful state just across the Potomac River from Washington. A secession convention already was meeting at the state capital. On April seventeenth, the convention voted to take Virginia out of the Union.

Virginia’s vote to secede forced an American army officer to make a most difficult decision. The officer was Colonel Robert E. Lee, a citizen of Virginia.

The army’s top commander, General Winfield Scott, had called Lee to Washington. Scott believed Lee was the best officer in the army. Lincoln agreed. He asked Lee to take General Scott’s job, to become the army chief.

Lee was offered the job on the same day that Virginia left the Union. He felt strong ties to his state. But he also loved the Union.

His decision will be our story in the next program of THE MAKING OF A NATION.

(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

You have been listening to the Special English program, THE MAKING OF A NATION. Your narrators were Stuart Spencer and Jack Moyles. THE MAKING OF A NATION can be heard Thursdays.