(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

THE MAKING OF A NATION — a program in Special English.

(MUSIC)

In July, eighteen-sixty-one, Union soldiers of the north and Confederate soldiers of the south fought the first major battle in America’s Civil War. They clashed at Manassas, or Bull Run, Virginia…less than fifty kilometers from Washington.

The Union soldiers fought furiously. But two large Confederate forces broke the Union attack.

I’m Kay Gallant. Today, Harry Monroe and I will tell about some of the other early battles of the Civil War.

VOICE TWO:

Northerners had expected to win the battle of Bull Run. They believed the Confederacy would fall if the Union won a big military victory early in the war. Now, however, there was great fear that southern soldiers would seize Washington. The Union needed to build and train an army quickly.

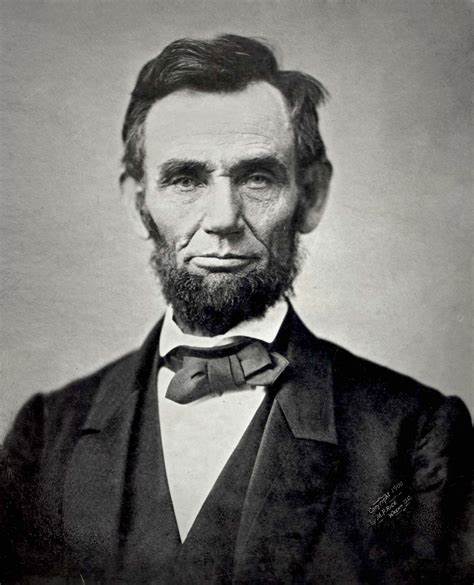

President Abraham Lincoln named General George McClellan to do this. McClellan was thirty-four years old.

The young general had two important tasks. He must defend Washington from attack. And he must build an army to strike at enemy forces in Virginia. McClellan wasted no time. He put thousands of troops into position around the city. And he built forty-eight forts.

After this rush of activity, however, little more happened for a long time. McClellan told his wife: “I shall take my own time to make an army that will be sure of success. As soon as I feel my army is well-organized and well-trained and strong enough, I will force the rebels to a battle.”

McClellan kept making excuses for why he would not move against the enemy. His excuses became a continuing source of trouble for President Lincoln. The public, the press, and politicians all demanded that McClellan do something. They wanted to win the war…and win it right away.

VOICE ONE:

McClellan commanded the biggest army in the Union, the Army of the Potomac. But it was not the only army. Others were battling Confederate forces in the west.

The Confederates had moved up through Tennessee into the border state of Kentucky. They built forts and other defensive positions across the southern part of the state. They also blocked as many railroads and rivers as they could.

Their job was to keep Union forces from invading the south through Kentucky. One of the Union Generals in the area was Ulysses Grant.

Grant had served in the army for twenty years. He had fought in America’s war against Mexico and had won honors for his bravery. When that war ended, he was sent to an army base far from his wife and children. He did not like being without them. And he did not like being an officer in peace time.

Grant began to drink too much alcohol. He began to be a problem. In eighteen-fifty-four, he was asked to leave the army. When the Civil War started, Grant organized a group of unpaid soldiers in Illinois. With the help of a member of Congress, he was named a General.

All of the other Union Generals knew Ulysses Grant. Few had any faith in his abilities. They were sure he would always fail.

VOICE TWO:

Grant, however, had faith in himself and his men. He believed he could force Confederate soldiers to withdraw from both Kentucky and Tennessee. Then he would be free to march directly into the deep south — Mississippi.

Two Confederate forts stood in Grant’s way. They were in Tennessee, close to the Kentucky border.

United States navy gunboats captured the first, Fort Henry, on the Tennessee River. That fort was easy to attack and not well-defended. The fighting was over by the time Grant and his men got there.

The second, Fort Donelson, was nearby on the Cumberland River. It was stronger and defended by twenty thousand soldiers. Grant surrounded the fort and let the navy gunboats shell it. The fighting there lasted several days.

VOICE ONE:

At one point, the Confederates tried to break out of the fort and escape. They opened a hole in the Union line and began to retreat. Suddenly, however, their commanding officer decided it would be wrong to retreat. He ordered them back to the fort.

After that, there was no choice. The Confederates would have to surrender.

The commanding officer sent a message to General Grant. “What were the terms of surrender?” Grant’s answer was simple. “No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender.”

The Confederates gave up Fort Donelson. Grant took fourteen-thousand prisoners.

It was the greatest Union victory since the start of the war. Ulysses Grant was a hero. Newspapers called him “Unconditional Surrender” Grant.

VOICE TWO:

After the Union victory at Fort Donelson, Confederate forces withdrew from Tennessee. They moved farther south and began to re-group at Corinth, Mississippi.

Confederate Generals hoped to build one big army to stop Ulysses Grant. They would have to move fast. Grant was marching toward Corinth with forty thousand men. Another thirty-five thousand, under the command of Don Buell, were to meet him on the way.

Grant arrived in the area first. He waited for Buell thirty kilometers from Corinth, near a small country meeting hall called Shiloh Church.

Confederate General Albert Sydney Johnston was waiting, too. He had more than forty thousand men, about the same as Grant. And he was expecting another twenty thousand. But when he learned that grant was nearby, he decided not to wait. He would attack immediately.

VOICE ONE:

Johnston did not know it, but his attack came as a surprise to the Union army. Union officers had refused to believe reports that Johnston was on the move. They said his army was not strong enough to attack.

Union troops did not prepare defensive positions. They had no protection when the battle began.

The fighting at Shiloh was the bitterest of the war. It was not one battle, but many. Groups of men fought each other all across the wide battlefield. From a distance, they shot at each other. Close up, they cut each other with knives. The earth became red with blood. The dead and wounded soon lay everywhere.

At first, the Confederates pushed Grant’s army back. They had only to break through one more line…and victory would be theirs. But in the thick of the struggle, General Johnston was shot in the leg. The bullet cut through an artery. Johnston bled to death before help arrived. Any hope for a southern victory at Shiloh died with him.

By the time the fighting began again the next day, General Buell had arrived to help Grant. The Confederate army retreated. The Union army let it go.

VOICE TWO:

Shiloh. The word itself came to mean death and destruction.

The battle of Shiloh had brought home to the American people — both of the north and south — the horror of war. It was the first time so many men — one hundred thousand — had fought against each other in the western world. It was the American people’s first real taste of the bloodiness of modern warfare.

As one soldier who fought there said: “It was too shocking, too horrible. I hope to God that I may never see such things again.”

The north won the battle of Shiloh. But it paid a very high price for victory. More than thirteen thousand union soldiers were killed, wounded, or missing. On the Confederate side, more than ten thousand soldiers were killed or wounded.

The north celebrated the news of its victory. But joy quickly turned to anger when the public learned of the heavy losses. People blamed General Grant. They demanded that President Lincoln dismiss him.

Lincoln thought of the two men who were now his top military commanders: McClellan and Grant. They were so different. McClellan organized an army….and then did nothing. Grant organized an army…and moved.

Lincoln said of Grant: “I cannot do without this man. He fights.”

(PAUSE)

We will continue our story of the Civil War next week.

(THEME)

VOICE ONE:

You have been listening to the Special English program, THE MAKING OF A NATION. Your narrators were Kay Gallant and Harry Monroe. Our program was written by Frank Beardsley.